|

ALL academics facilitating articulated learning for English as an additional language students

Richard N Warner and Michelle Y Picard

University of Adelaide

This paper develops the concept of articulated learning and relates it to the role of Academic Language and Learning (ALL) academics in facilitating the progress of international and other English as an additional language (EAL) students from program to program, between generic, academic and disciplinary skills and from their studies to the work environment. It also describes the ALL role in the development of reflective learning practices which are essential to enable students to problem-solve both academically and professionally. We combine these two elements to extend the theory of articulated learning and explore its value in the internationalisation of higher education. Although it is impossible to detail the vast array of ALL contexts and practices in Australian and international contexts, the case study exemplified in this paper by the Introductory Academic Program enables a clearer definition of the role of ALL practitioners and how they, along with disciplinary counterparts, can best facilitate student learning and achievement.

The aim of this paper is to outline a specific aspect of the ALL academic's role: creating the conditions in which students can progress in their studies and future careers and develop the skills to reflect on learning in a coherent fashion. These aspects relate to our synergetic concept of articulated learning and our description of the way ALL academics operate within the changing academic landscape. We focus particularly on the English as an additional language (EAL) student cohort, using the University of Adelaide Introductory Academic Program (IAP) as a case study. In the following sections, we describe the changing university context in Australia and the resulting challenges for ALL academics and EAL students. We then define the different concepts of articulated learning and relate these to policy and practices in the Australian context. Finally, we describe the University of Adelaide and the IAP as a case study exemplifying the ALL role in relation to articulated learning. Although this paper focuses upon an Australian case study, it offers a transferable international model for facilitating articulated learning.

Pertinent to the development of such Graduate Attributes, the role of ALL academics in assessing and providing ongoing structured development of English language proficiency in EAL learners has been highlighted in the Good Practice Principles for English Language Proficiency for International Students in Australian Universities report (Arkoudis et al., 2009). The best practice principles have now been embedded in the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency regulatory and quality insurance standards and processes for education providers in Australia.

The English language entrance requirements for international EAL students are such that they need to achieve 6 or 6.5 overall in the International English Language Testing System (IELTS) or equivalent examinations. Thus they have a 'generally effective command of the language, despite some inaccuracies, inappropriacies and misunderstandings' (IELTS, 2012). However, the Graduate Attributes they require on exiting their programs necessitate a far higher level of English than that achievable by students who are still mastering the subtleties of the language. Additionally, since students often focus on disciplinary content rather than English language post-enrolment, their English proficiency can actually decline over the course of their degrees (Birell, 2006; Birell & Healey, 2008). Accountancy firms, in particular, have noted the difficulties in professionally placing EAL graduates who obtain permanent residence. It has been suggested that these difficulties are primarily due to their English language weaknesses (Birell & Healey, 2008).

Following on from the work of Birell and Healy (2008), in a detailed study on IELTS performance, Craven (2012) found that EAL students who originally met the language requirements and were accepted into university for undergraduate degrees, did not reach IELTS 7.0 scores at the end of their degree programs as required by a number of professional bodies (e.g. Accountancy and Nursing). This could frustrate their immediate goals of gaining employment and permanent residence in Australia. Such a score might be seen to equate to student proficiency in English as approximating the level of language ability necessary to operate in that profession. However, language ability is but one element of modus operandi in the professional world. The attainment of Graduate Attributes and professional articulation for EAL students also requires the development of certain ways of thinking and being which are privileged in western academia and professional contexts (Gee, 2004). Communicating in a way that is rewarded in this context can be particularly challenging for EAL students who may lack the necessary 'cultural capital' (Bourdieu, 1973, p. 46). Closely aligned with this is the fact that many international EAL students enter Australian universities for the first time at a postgraduate coursework or research level. They not only lack the linguistic and cultural background of their Australian counterparts, but they also have not had the same undergraduate experiences. Thus, it is clear that ensuring effective articulation from program to program and from university to the professional world has become a vital emphasis in the university education of EAL students, as it is for all students. Factors influencing professional articulation are an important element of cultural capital which needs to be explicitly addressed for EAL learners.

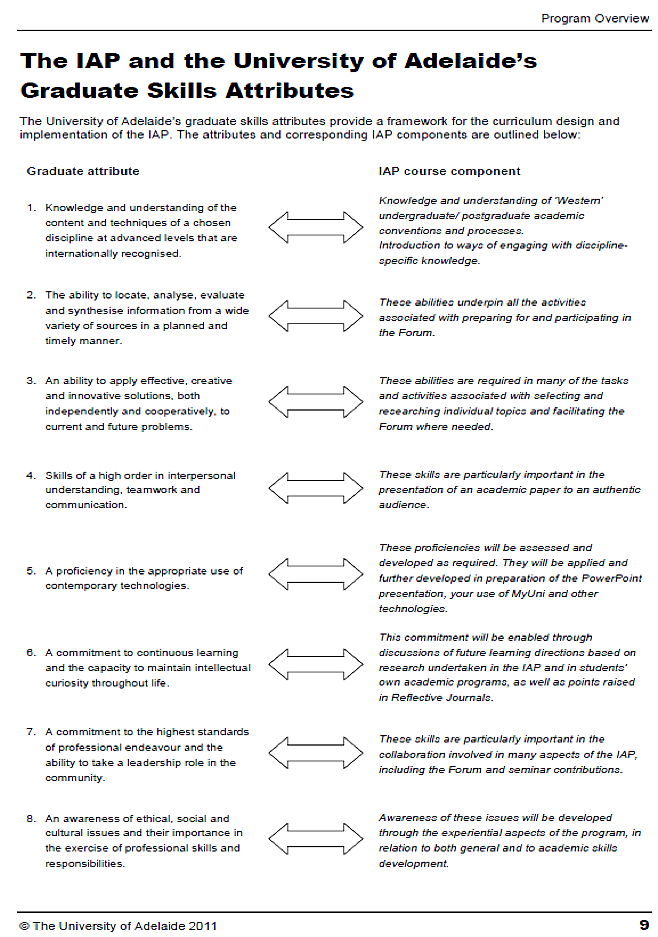

Other aspects affecting student articulation are the expectations of the knowledge economy (Dunning, 2000) which are reflected in Graduate Attributes. Graduates are able to adapt to change, embark on 'continuous learning', be 'innovative' and 'creative' and have an awareness of 'ethical, social and cultural issues within a global context and their importance in the exercise of professional skills and responsibilities' (University of Adelaide, 2011). Ash, Clayton and Atkinson (2005, p.50) describe how the structured development of reflective practices 'supports students in achieving and demonstrating [high level] academic and cognitive outcomes as well as outcomes with respect to personal growth and civic engagement'. Facilitating reflection in and on action and effective communication of this reflective process are thus other essential elements requiring attention for all learners, and are an important element of cultural capital which needs to be explicitly addressed for EAL learners.

Although Graduate Attributes relate to the generic skills required for graduates to move from course to course and from courses to professional life, they also include a focus on individual growth (Barrie, Hughes, & Smith, 2009). Reflection, for example, is a vital element in attaining these attributes and consequently functioning as an effective student and professional. A landmark paper by Ash and Clayton (2004) first described reflective practice as articulated learning. In their paper, they demonstrate how students are able to connect 'their experiences [in practical work-related environments] to course material', challenge their beliefs and assumptions and deepen their learning through a scaffolded reflective process that assists them to articulate or communicate and act on their learning (Ash & Clayton, 2004, p.11). This articulated learning process involves three main phases: 1) description (objectively) of an experience, 2) analysis in accordance with relevant categories of learning, 3) articulation of learning outcomes. We believe that ALL academics can play a vital role in these aspects of articulated learning for EAL learners: their scaffolded progression within and beyond university in terms of language and cultural learning and the development of their ability to reflect and communicate such reflections on learning.

In Australia, the Higher Education agenda has increasingly emphasized the first definition of articulated learning in relation to effective articulation from high school to Technical and Further Education (TAFE) or university or from undergraduate to post-graduate studies as part of its widening participation agenda (Thomas, 2001). This agenda, as described in the Bradley Review into Australian Higher Education (Bradley et al., 2008), aims to dramatically increase the participation of all Australians, particularly those of low-socio economic status (SES) or from families previously uninvolved in higher education in university studies. To facilitate this articulation, the review proposed changes to the funding model, 'outreach activities in communities with poor higher education participation rates' (Bradley et al., 2008: XIV) and partnerships between schools, the TAFE sector, and universities to ensure seamless articulation. The review also tasks institutions to 'work to raise aspirations as well as provide academic mentoring and support' (Bradley et al., 2008, p. XIV). ALL practitioners play a central role in providing this support, since low SES and other non-traditional students are 'heavy users of academic ... support services' (Bradley et al., 2008, p. 42). Therefore, the report recommends that extra resources should be provided for them. ALL resources provided as part of the widening participation agenda have included one-on-one writing assistance in writing centres, workshops on generic academic issues and around particular assignments, embedded language and learning as part of the curriculum of core subjects, and a range of collaborations between disciplinary and ALL academics around enhancing the first year experience.

Like non-traditional, low SES Australians, international EAL learners have similarly benefitted from the support services described above and studies reveal a high usage of ALL support among international EAL students (Ransom, Larcome & Baik, 2006). However, as noted earlier, these students may have additional needs since they have not benefitted from local articulation efforts to assist them in their progression from school or other pathways to university and from undergraduate to postgraduate studies. In many cases, they commence their studies in Australia at a postgraduate level. Thus, in addition to the challenges of communicating complex thought in their additional language, these students also face issues related to differences in academic cultures. In working with international and even local EAL students, lecturers and ALL academics in particular need to convey 'the interrelationship and continuity of contents, curriculum, instruction, and evaluation within programs which focus on the progress of the student in learning both to comprehend and communicate in a second language' (Lange, 1988, p.10) into account. This aspect of articulation is addressed by ALL academics through a range of different practices, including some specifically focussing on language and cultural issues which are described in more detail under the headings of ALL contexts and practices.

The third reflective aspect of articulation is closely linked with the first two in the Australian context, since reflection is a vital element in attaining Graduate Attributes and consequently functioning as an effective professional, as is described by Ash and Clayton (2004) when they discuss the role of reflection in professional learning.

In the following sections, we describe how ALL academics aim to assist EAL students in all aspects of articulated learning: the progression of their studies and career, the movement from generic to disciplinary skills and the reflection on and expression of their learning in a coherent fashion. Although it would be impossible for ALL practitioners to facilitate a quick fix of all the language and academic cultural issues challenging EAL learners, their explicit unpacking of articulated learning processes can help these students to identify their strengths and weaknesses, develop the traits and skills required by their disciplinary courses and future careers, explore decisions made and actions taken and 'consider alternative approaches and interpretations' (Ash & Clayton, 2004, p.14). They are also able to examine 'the sources and significance of assumptions or interpretations regarding those different from themselvesÉ and to evaluate strategies for maximising opportunities and minimizing challenges' (Ash & Clayton, 2004, p.14). Thus, they are empowered to set up personal learning plans and take control of and responsibility for their own learning.

The work of the ALL Unit at the University of Adelaide includes a number of the academic development contexts and practices listed above, recognising that 'the increasingly inter- and multi-disciplinary nature of degree programs requires more students to manage discourse and register expectations across discipline areas' (Warner, 2010, p.1). EAL students need to be able to access such content via code-breaking practices in relation to both discourse patterns and academic expectations in order to attain positive learning outcomes. As Warner (2010) notes, such code-breaking is multi faceted and can be seen to operate at a minimum of two levels, the first being at the level of the broader academic tradition, with the second focussing on the dominant patterns of discourse within specific disciplines.

ALL academics in the School of Education provide (what might be termed) academic generic pathways to help EAL students to both reflect upon and decode the system and its inherent values and expectations, as a precursor to their decoding of disciplinary discourse patterns. Yet ALL academics also play an increasingly prominent role in academic disciplinary contexts, working directly with faculty academics in the delivery of their courses. This includes such activities as tutorials and team teaching embedded within the courses themselves. These embedded scenarios can also provide opportunities for professional articulation, as the tasks themselves relate to communicative interactions, such as report writing to a hypothetical external organisation, which require those interpersonal skills outlined in the Graduate Attributes.

As outlined in Table 1, the learning pathways aim to provide the scaffoldings necessary for EAL students to become self-reflective autonomous learners, with greater cultural capital (Bourdieu, 1973) and with the ability to decode systemic values, expectations and practices. This enables the students to make better engagement with disciplinary communication and language patterns. The ALL Unit practices recognise that the EAL learner has to be able to articulate from program to program (and sometimes from discipline to discipline) effectively within the university context and onwards into the professional world. These varied practices are highly demanding of the student and necessitate the scaffolded development of reflection, permitting the EAL learner to 'integrate the understanding gained into [their] experience ... to enable better choices or actions ... as well as enhance [their] overall effectiveness' (Rogers, 2001, in Ash & Clayton 2004, p.137).

| Learning pathway | Academic generic | Academic disciplinary | Professional articulation |

| Writing centre (1-1 with tutor) |  |  | |

| Faculty writing centres (in conjunction with faculties) |  |  |  |

| Small group with tutor (at student request) |  |  | |

| Semester series seminars |  | ||

| Writing and Speaking at University (My Uni modules) |  |  (some modules are subject specific) | |

| Learning Guides |  |  (includes specific guides to widely used referencing systems) | |

| In faculty workshops/ consultancies |  |  | ? |

| Introductory Academic Program |  |  | |

| Orientation Sessions |  |  | |

| Conversation classes |  |

This model aims to empower the students to take increasing control over their learning as the course develops. In the IAP, the lecturers begin the program in a more traditional role, setting the non-negotiable tasks (as outlined later) and take upon direction and assessment of the initial activities. Students learn through accretion (Enomoto, 2011) and the initial scaffolding in the IAP provides such accretion via incremental staging to mentor students through tasks. This scaffolding has to be challenging enough to promote self-regulated learning but without being too daunting so as to impinge upon their academic self-efficacy (Habel, 2009), since this could potentially precipitate a return to erstwhile learning strategies, perhaps less appropriate to their contemporary academic environment. As the IAP develops, students in this action teaching environment, take increasing control of the learning process with a simultaneous change in the lecturer's role from one of direction to that of facilitation.

Figure 1: The action teaching spiral in the IAP (After Cadman and Grey, 1997, p.6)

The IAP maintains a focus on reflective practice in the context of a highly articulated learning environment. Each course component is explicitly mapped out in the student handbook against the university Graduate Attributes (2011, see Appendix 1), thus providing conceptual points of comparison to their future discipline based courses. An early reflective task in the IAP, as part of the action teaching spiral, involves a discursive activity based around this Graduate Attribute mapping. Students are also highly encouraged to complete a long term personal learning plan (PLP), the pro forma of which is again mapped out against the University Graduate Attributes (2011). Further built in reflection in the IAP takes the form of a weekly reflective journal for lecturer response which is submitted through the university teaching management system, discussion threads based around aspects of the major course task-writing, and presenting a critical review.

The critical review allows students to begin to connect the academic generic with the academic disciplinary elements of study. Students are given single journal articles in their subject areas, provided by their postgraduate course coordinators or research supervisors. The students then interrogate, using other (self-selected) sources, in order to submit a subject specific critical review of their assigned article at the end of the course. As part of this process, they reflect on their review development through a number of different mechanisms. These include feedback, written and oral (voice tool and one-on-one discussions) on their drafts, peer reflections on their work and in-class sessions on dimensions of critical writing.

Reflection is also part of the process leading up to the oral presentation of their critical reviews at the IAP forum. The ALL Unit provides the facilities and equipment, everything else is the responsibility of the students themselves, including theme, organisational groupings, running order, invitations and plenary speakers. As part of taking ownership of their learning, students need to arrange regular meetings to reflect on what has been done, what needs to be done and how things can be improved. Participation in the IAP forum is designed to be an empowering process for the students. The forum itself follows a typical academic conference scenario, beginning with a plenary session in a large lecture theatre, based round the forum theme, in which a senior academic from the university (invited by the students) is introduced as a guest speaker. The students then present their critical reviews in concurrent sessions, which are usually thematically determined, and hosted by the students in other proximate rooms. These are attended by the invitees, including academics and professional staff, both involved in the IAP itself, but also can include academics from their discipline areas. At the end of the day, the students return to the lecture theatre for a final plenary session. This also involves the input of a guest speaker, again usually an academic or professional member of the university staff, who has had significant involvement in the program. A recent trend, which seems indicative of the students' appreciation of the relevance of the value of reflection, is the incorporation of a forum debriefing session, on the following day. During this session, which has been inaugurated by the students themselves, the students discuss what they learned from the experience, how successful they perceive the forum to have been and how they might have done it differently.

The emphasis on reflection and empowerment also continues after the completion of the IAP. Towards the end of the first semester, an email call is sent out asking students, who have recently completed the IAP and have had several weeks study experience in their faculties, if they would like to be volunteers for a focus group session. This focus group, usually between six to eight students, takes the form of a semi-structured discussion, which is recorded, where the students reflect on the relevance of the IAP to their study experiences in faculty. The discussions are facilitated by two academic staff from the IAP. These reflections are than fed back into the development of the curriculum and, over the years the program has been running, have had a significant impact on the delivery and content of the IAP.

The IAP therefore aims to help engage the students into their new academic environment, providing articulated pathways into the demands of their own discipline areas. Yet, at the same time, the program is not exclusively academic generic - IAP students begin explorations in their own fields of study. Moreover, professional development is articulated through the mapping of program elements to the University Graduate Attributes (2011), thus aiming to enable IAP students to make conceptual connections with their future courses and career pathways.

Ash, S. & Clayton, P. (2004). The articulated learning: An approach to guided reflection and assessment. Innovative Higher Education, 29(2), 137-154. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:IHIE.0000048795.84634.4a

Ash, S., Clayton, P. & Atkinson, M. (2005). Integrating reflection and assessment to capture and improve student learning. Michigan Journal for Community Service-Learning, 11(2), 49-60. http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/contentdelivery/servlet/ERICServlet?accno=EJ848474

Barrie, S. C. (2004). A research-based approach to generic graduate attributes policy. Higher Education Research & Development, 23(3), 261-275. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0729436042000235391

Barrie, S. C., Hughes, C. & Smith, C. (2009). The National Graduate Attributes Project: Integration and assessment of graduate attributes in curriculum. University of Sydney and Australian Learning and Teaching Council. http://www.itl.usyd.edu.au/projects/nationalgap/introduction.htm

Barthel, A. (2010). Table of Australian ALL centres and units. Association for Academic Language and Learning. http://www.aall.org.au/sites/default/files/ALLservicesTypes2010.pdf

Birrell, B. (2006). Implications of low English standards among overseas students at Australian universities. People and Place, 14(4), 53-54. http://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=332480460154352;res=IELHSS

Birrell, B. & Healy, E. (2008). How are skilled migrants doing? People and Place, 16(1), 1-20. http://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=157423695183563;res=IELHSS

Bourdieu, P. (1973). Cultural reproduction and social reproduction. London: Tavistock.

Braband, C. (2008). Constructive alignment for teaching model-based design for concurrency. In K. Jensen, W. van der Aalst & J. Billington (Eds), ToPNoC I, LNCS 5100, 1-18. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-89287-8_1

Bradley, D., Noonan, P., Nugent, H. & Scales, B. (2008). Review of Australian Higher Education. Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. http://www.innovation.gov.au/HigherEducation/ResourcesAndPublications/

ReviewOfAustralianHigherEducation/Pages/ReviewOfAustralianHigherEducationReport.aspx

Cadman, K. & Grey, M. (1997). Action teaching: Student-managed English for academic contexts. Gold Coast, Queensland: Antipodean Educational Enterprises.

Cadman, K. & Grey, M. (2000). The 'Action Teaching' model of curriculum design: EAP students managing their own learning in an academic conference course. EA Journal, 17(2), 21-36.

Craven, E. (2012). The quest for IELTS Band 7.0: Investigating English language proficiency development of international students at an Australian university. IELTS Research Reports 13, 1-61. http://www.ielts.org/PDF/vol13_Report2.pdf

Dunning, J. (Ed.) (2000). Regions, globalization, and the knowledge-based economy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Education.com.inc (2006-2011). Glossary of Education: Articulation. http://www.education.com/definition/articulation-education

Enomoto, K. (2011). Fostering high quality learning through a scaffolded curriculum. In C. Nygaard, N. Courtney & C. Holtham (Eds), Beyond transmission: Innovations in university teaching. Oxfordshire: Libri Publishing.

Gee, J. (2004). An introduction to discourse analysis: Theory and method. London: Routledge.

Habel, C. (2009). Academic self-efficacy in ALL: Capacity-building through self-belief. Journal of Academic Language and Learning, 3(2), A94-A104. http://journal.aall.org.au/index.php/jall/article/download/96/79

IELTS (2012). The International English Language Testing System (IELTS). http://www.ielts.org/

Lange, D. (1988). Articulation: A resolvable problem? Shaping the future of foreign language education: FLES, articulation, and proficiency. In J. Lalande (Ed.), Reports of the Central States Conference on the Teaching of Foreign Language. Lincolnwood: National Textbook.

Marginson, S. (1997). Competition and contestability in Australian higher education, 1987-1997. Australian Universities' Review, 40(1), 5-14. http://www.nteu.org.au/library/view/id/672

O'Regan, K. (2005). Theorising what we do: Defamiliarising the university. In S. Milnes, G. Craswell, V. Rao & A. Bartlett (Eds.), Critiquing and reflecting: LAS profession and practice: Proceedings of the 2005 Australian Language and Academic Skills Conference. Canberra: Australian National University. http://www.aall.org.au/sites/default/files/las2005/oregan.pdf

Ransom, L., Larcome, W. & Baik, C. (2006). English language needs and support: International-ESL students' perceptions and expectation. Language and Learning Skills Unit, University of Melbourne, Victoria, 3010, Australia. http://services.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/471374/ransom-larcombe-baik.pdf

Roe, E., Foster, G., Moses, I., Sanker, M. & Storey, P. (1982). A report on student services in tertiary education. Brisbane: University of Queensland.

Thomas, L. (2001). Widening participation in post compulsory education. New York: Continuum.

University of Adelaide (2011). 2010 Pocket Statistics. http://www.adelaide.edu.au/research/about/facts/

University of Adelaide (2012). 2011 Graduate Attributes. http://www.adelaide.edu.au/dvca/gradattributes/

Velautham, L. & Picard, M. (2009). Collaborating equals: Engaging faculties through teaching-led research. Journal of Academic Language and Learning, 3(2), A130-A141. http://journal.aall.org.au/index.php/jall/article/view/89/78

Warner, R. (2010). It's all Greek to me! 'Learning Guides' as pathways to academic literacy for international students at the University of Adelaide, Australia. Paper presented at ESP/ EAP Innovations in Tertiary Settings: Proposals and Implementations. 2nd ESP/EAP Conference, Kavala Institute of Technology, Greece.

| Authors: Richard Warner is a lecturer in the Discipline of Higher Education, School of Education, The University of Adelaide, Australia. Much of his teaching is based around the acculturation of coursework and research, postgraduate international students, into the university culture. His research interests include feedback as a cultural entity, academic transitions and reflective learning. Email: richard.warner@adelaide.edu.au Dr Michelle Picard is Director of Researcher Education, MEd Coordinator and Senior Lecturer, Discipline of Higher Education, School of Education at the University of Adelaide. Her research interests cover educational technology, doctoral writing, language and learning across the curriculum, international postgraduate student perspectives and academic integrity. Email: michelle.picard@adelaide.edu.au Please cite as: Warner, R. N. & Picard, M. Y. (2013). ALL academics facilitating articulated learning for English as an additional language students. Issues in Educational Research, 23(1), 83-96. http://www.iier.org.au/iier23/warner.html |