|

Applying the Kirkpatrick model: Evaluating an Interaction for Learning Framework curriculum intervention

Megan Paull, Craig Whitsed and Antonia Girardi

Murdoch University, Australia

Global perspectives and interpersonal and intercultural communication competencies are viewed as a priority within higher education. For management educators, globalisation, student mobility and widening pathways present numerous challenges, but afford opportunities for curriculum innovation. The Interaction for Learning Framework (ILF) seeks to help academics introduce curriculum change and increase peer interaction opportunities. Although the framework has many strengths to recommend it, the ILF does not provide a process by which academics can easily evaluate the outcomes produced by its implementation. In this paper, we examine the efficacy of a popular four level training evaluation framework - the Kirkpatrick model - as a way to appraise the outcomes of ILF-based curriculum interventions. We conclude that the Kirkpatrick model offers educators a straightforward basis for evaluation of interventions, but that as with any model the approach to evaluation should be adapted to the particular setting and circumstances.

Of the total 230,923 international student enrolments in 2012, just over a quarter were studying a Masters degree by coursework and half of these were in management and commerce - almost four times that of the next closest field of study (Chaney, 2013, p. 11-13). This student profile has forced attention towards the curriculum and learning outcomes for the globalised professional labour market and teaching environment, which embrace increased intercultural skills development for graduates. This is not confined to the Australian setting (c.f. Mintzberg & Gosling, 2002; Schlegelmilch & Thomas, 2011).

There is growing recognition that traditional approaches to curriculum, teaching and learning may not be addressing needs of the increasingly diverse student population, or satisfying the demands of graduate employers (Australian Business Deans Council, 2014; Dyllick, 2015). The changing student population necessitates new approaches to both curriculum design and teaching that specifically aim to scaffold learning by drawing on and building student capability. Academics teaching in postgraduate management education programs need to acknowledge the changing student demographic and harness this opportunity.

International and domestic students alike are understood to benefit from opportunities which encourage development of generic business attributes, support students to think globally, and value cultural and linguistic diversity (Green & Whitsed, 2015; Leask, 2008). Learning environments that foster peer interaction can better prepare students for globalised workplaces. One way to draw on student diversity is to focus on peer interactions within a structured learning environment. Enhancing interaction between students in an on-campus class is, however, challenging (Harrison, 2015; Kimmel & Volet, 2012). The Interaction for Learning Framework (ILF) developed in Australia by Arkoudis et al., (2010) is intended to help academics structure learning environments which increase interaction between students.

Although the ILF provides a basis for planning innovations in learning environments to increase peer interaction, there is a need for evaluation of the implementation of this framework. In addition to "raising the awareness of academics about the possibilities for improvement" (Arkoudis, et al., 2013, p. 233), it is necessary to provide evidence of intervention outcomes. One appraisal tool in business (see Han & Boulay, 2013), and recently employed in higher education (Praslova, 2010; Taras, et al., 2013), is the Kirkpatrick four level training evaluation model (Kirkpatrick & Kayser-Kirkpatrick, 2014).

This paper is an account of the evaluation of the curriculum innovation grounded in the ILF. We examine the efficacy of the popular four level training evaluation framework - the Kirkpatrick model - as a way to appraise the outcomes of ILF-based curriculum interventions.

Amoroso, Loyd and Hoobler (2010, p. 796) argued, "management educators play an important role in exposing students to many diversity related topics". They maintained that strategic pedagogical approaches need to be employed to mitigate the problems arising from common diversity discussion-based practices, which have a tendency to reinforce status group boundaries and affirm stereotypical beliefs. As Amoroso et al. (2010) suggested, structuring activities which promote new allegiances and social identities, and undermine stereotyping, are an important part of the educators' role.

There has been increased attention paid to the 'internationalisation of the curriculum' as a way of developing global perspectives (Leask, 2008; Leask & Beelen, 2009; Wamboye, Adekola & Sergi, 2015). Across this literature, three essential educational requirements are emphasised. First, learning environments need to be structured to provide students with opportunities to develop intercultural competencies as a feature of the formal curriculum (Leask, 2008; Leask & Beelen, 2009). While this goal has been characterised as an impossible 'ideal' (DeVita, 2007), it is nevertheless an important aspirational goal, particularly as it relates to graduate capability and learning outcomes (Caruana & Ploner, 2010). Second, learning environments need to facilitate the development of generic graduate attributes such as: thinking globally; appreciating multicultural diversity; valuing cultural and linguistic diversity (Leask, 2008); cultural intelligence (Shaw, 2004); and, specific disciplinary knowledge. Third, learning environments need to encourage and support peer interactions (Arkoudis, et al., 2010; Schullery & Schullery, 2006) and productive engagement in teams (Volet & Mansfield, 2006; Kimmel & Volet, 2012).

Denson and Bowman (2011) suggest it is not only the quantity, but the quality of interactions between culturally diverse peers, that is important for the development of intercultural communication competencies (see also Harrison, 2015). Kimmel and Volet (2012, p. 449) observed, "despite all the potential beneficial effects of group work in academic learning, there is a parallel, strong and converging body of literature documenting students' negative perceptions... and experiences of socio-emotional as well as socio-cultural challenges". Osmond and Roed (2010) concluded that most students tend to prefer homogenous groups with similar backgrounds, shared languages or shared difficulties with English as a second language. The tendency for students to avoid interacting with others they perceive to be dissimilar to themselves (Harrison & Peacock, 2010), provides a significant rationale for curriculum innovation that encourages engagement between all students.

According to Arkoudis et al., (2010, p. 26), "internationalising teaching and learning strategies, including increasing interaction between domestic and international students" is a key challenge. The degree to which educators purposefully manage interpersonal and intercultural interaction is still relatively unknown. Likewise, how students respond when these dimensions of learning are structured into the learning environment is also largely under-researched. Research to evaluate resources intended to innovate curricula to support such learning outcomes is equally rare (Green & Whitsed, 2013).

Arkoudis et al., (2010) stressed it is false to assume that productive peer interaction will spontaneously occur in classes without structured interventions. Encouraging structured peer interaction in learning environments is viewed as a potential means to engender productive outcomes. This is the focus of the Interaction for Learning Framework (ILF).

Although the framework has many strengths to recommend it, the ILF does not provide a process by which academics can easily evaluate the outcomes produced by its implementation. Evaluation of teaching interventions cannot easily be parsed, nor can academic staff, with increasing time constraints, afford to spend hours conducting in-depth evaluation of innovative approaches to teaching. We present the Kirkpatrick model as a simple, time efficient way to evaluate the outcomes of ILF-based curriculum interventions.

The Kirkpatrick model has been employed in higher education settings with varying opinions about its efficacy (see Abdulghani, et al., 2014; Arthur, Tubre, Paul & Edens, 2003; Chang & Chen, 2014; Collins, Smith & Hannon, 2006; Praslova, 2010; Yardley & Dornan, 2012). Although Saks and Haccoun (2010) concluded it may not be well-suited to formative evaluation, and Holton (1996) and Alliger, Tannenbaum, Bennett, Traver & Shotland (1997) have criticised the hierarchical nature of the approach, these conclusions have not been further substantiated, nor had an impact on its application in industry. Its simplicity and focus, and its systematic approach, mean that it remains one of the most widely used tools for evaluation of workplace training. It therefore provides a useful starting point for evaluation of curriculum innovations such as those proposed by the ILF. It is also likely to be familiar to management academics. What follows is a description of an ILF-based curriculum innovation in a postgraduate coursework business unit.

| Level | Description | |

| 1 | Reaction | Sometimes referred to as happy or smile sheets, this level of evaluation considers whether the participants reacted favourably to the training or intervention. |

| 2 | Learning | Related to learning outcomes of the training or intervention, this level considers whether the participants acquired the intended knowledge, skills or attitudes based on their participation in the training or intervention. |

| 3 | Behaviour | Sometimes referred to as 'transfer', this level considers the degree to which the participants altered their subsequent behaviour in other contexts (e.g. in the workplace) after participating in the training or intervention. |

| 4 | Results | Sometimes referred to as organisational level evaluation, and related to the longer term outcomes anticipated, this level considers whether the overall aims have been achieved as a result of the interventions, and of subsequent reinforcement. Rather than return on investment (ROI), the fourth level refers to return on expectations (ROE). |

The compulsory postgraduate unit, on organisational behaviour, has a diverse student cohort. In this particular semester, students (N=45) ranged in age from early 20s to 65; and from limited work experience to many years in a range of industries (e.g. health, teaching, mining, public and non-profit sectors) and professions (e.g. accounting, hospitality, human resources and marketing). This diversity extended to ethnic backgrounds, with students from Africa, Asia, Europe, and the United States. The domestic student cohort, many of whom had ethnic origins similar to the international students, included students from regional Western Australia and across the nation. All students were faced with challenges in managing their studies as part of their busy lives.

Supporting the development of students' intercultural communication competencies was a key learning objective in the unit. Students were required to self-select into groups to complete an assignment that extended over a number of weeks. Each group was required to develop a behavioural contract to establish their ground rules for working together. Students were also required to keep a critical incident log to document their group's evolution. A key element of the group assignment was the allocation of in-class time for students to work together. This allowed monitoring of groups and feedback provision by A1.

Observations by A1 over a number of semesters, however, had suggested the degree of interaction between the students in group projects and during class time was less than optimal, despite the interactive learning and group activities in place. For example, students repeatedly sat in the same location and in the same homogenous groups even though diversity was promoted as an ideal to be achieved in the group formation. Therefore, as a move to address this tendency, a series of interventions were undertaken using the ILF as a guide.

Adopting the ILF was intended to increase interactions between all students in the class. The aims were to enhance cross cultural communication, group interaction, communication and learning about diversity; and to help create social connections between students to enable peer support and reduce some of the barriers which are known to exist between domestic and international students.

To address the first two dimensions of the ILF - planning interactions and creating environments for interaction, A1 integrated the following into the unit's design and delivery.

Dimension four of the ILF relates to subject knowledge. The unit included topics such as perception, group dynamics, cultural differences and diversity. Class exercises were designed to specifically illustrate these and capitalise on student diversity. These included: a game of 'whispers' in the communication session; student conflict scenario discussions in the conflict session; and a blindfold exercise in the leadership session.

Training tools (e.g. playing cards) were used to randomly assign students to activity groups. In most sessions, groups formed by randomisation were required to discuss short cases, ethical dilemmas or management-practice scenarios drawing on their own experiences and understandings, in addition to the course materials.

As the semester ended, the students were invited by A2 to provide anonymous written responses to questions about their experiences. As part of the consent process, students were assured that comments would not be revealed to either A1 or A2 until all grades were finalised. In total 42 out of 45 students participated. The questions focused on student perceptions of assignment work in diverse groups; the manner in which groups were formed; general observations about other class exercises; and whether they maintained contact with each other outside class. Students rated whether they would be more inclined to participate in diverse group work in the future as a direct outcome of their experiences in the unit via a five point rating scale. Several students chose to add additional feedback comments.

The multi-source data allowed for evaluation according to the Kirkpatrick levels:

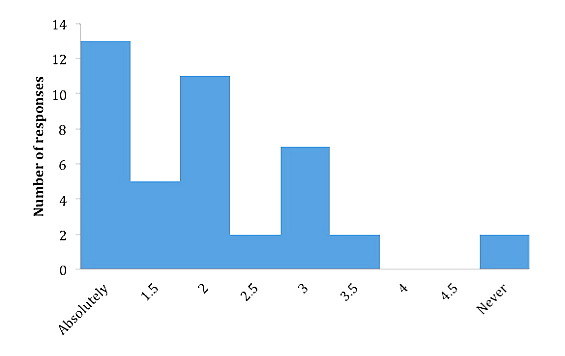

Figure 1: Student willingness to participate in similar group assignments

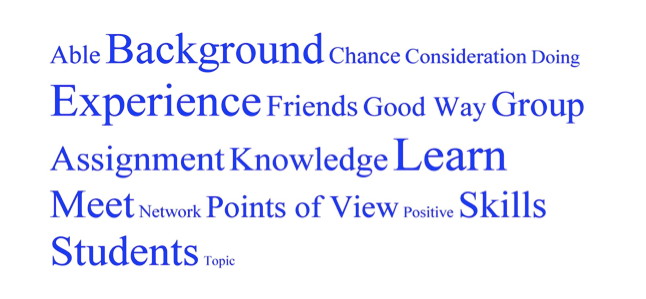

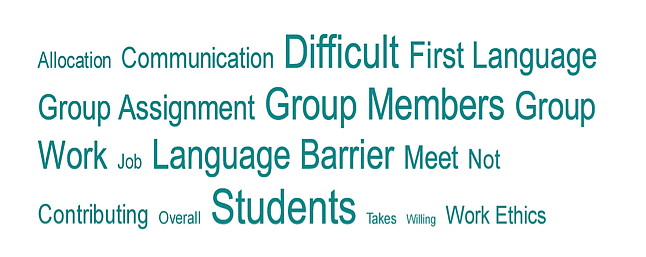

Feedback was generally positive. Those who overcame their initial reservations acknowledged the value of working in groups; and of interaction across a broad range of activities. Some of their comments are reflected in the frequency word pictures (see Bock, 2009) in relation to the positives (Figure 2) and negatives (Figure 3) of the methods employed.

Figure 2: Student perceptions of the approach: Positive

Figure 3: Student perceptions of the approach: Negative

A1 observed there were several students who were apathetic towards being randomly assigned to groups for in-class exercises, and a few initially declined to participate. More participated as the semester progressed, and tended to withdraw only from activities which required them to leave their seat, but not from small 'sit-down' discussion type activities.

Increased interaction between all students

Overall, student responses suggested an appreciation of the importance of being able to work in diverse groups and across cultural boundaries. The view was expressed by many students that this reflected the workplace as they perceived and experienced it.

The tendency among many students to shy away from interaction with others they perceive to be dissimilar, provides a significant rationale for curriculum innovation that encourages intra-cohort engagement. While it was not clear that this form of reluctance occurred in the unit, the randomised assignment to activity groups encouraged interaction where this might not otherwise have occurred.

Responses regarding group formation also tended to be positive, indicating high satisfaction levels with the manner in which groups were organised. One student remarked, "The heterogeneous mix of ethnicity and languages also contributed to the positives of group work."

Some students expressed reservations about group formation, and one likened it to a game of chance. Volet and Mansfield (2006, p. 342) observed that "even minimal levels of cooperation can present motivational and socio-emotional challenges, raising concerns about students' readiness for teamwork". They further observe that numerous empirical studies within the social-cognitive perspective, link student motivational factors to personal goals and "perceptions of appraisals of group assignments" (p. 342). It is possible that because marks had been allocated for the group assessment at the time of data collection, these may have influenced some of these responses.

As expected, not all responses were positive and several students were critical concerning the value to them of working in diverse groups. For instance a few students expressed the view that the activities were not appropriate use of their time. The receipt of negative criticisms suggests some students felt sufficiently empowered to offer this feedback. As with any survey, we are mindful of potential response bias with these and other results presented.

Enhanced learning

Student motivation to engage in a learning task is indexed to their appraisals of task valence, such as the value of group work. Therefore, it is necessary for the task to be recognised by students as important and that it be 'worth doing' (Leask & Carroll, 2011, p. 655). In addition to the intrinsic valence, the assessment was worth 30% of the final grade for the unit. Students were required to participate in small groups to complete some assigned learning tasks. The majority of students maintained that participating in the group assignment was overall a positive experience because of the insights, perceptions and skills afforded them by working within a diverse group.

Positive feedback was also received about the in-class activities designed to promote interaction beyond the assignment groups. The majority view was that these activities were enjoyable and could be employed in other units. Some of the feedback indicated that students understood the value of interaction for learning.

Collaboration [in the] groups in class is fantastic to meet students and discuss the course content. It helps the understanding of the content and gives you confidence that your opinions are valid and relevant.Students were asked to rate their willingness to participate again in a group assessment if the task were similarly structured and managed. Two students indicated 'never again' with 13 indicating absolute willingness. The results indicate that the students endorsed the manner in which the assessment tasks and other activities were constructed and contributed to engendering positive attitudes towards working with others. Research suggests that curriculum innovation which promotes team-work and team interaction increases learning opportunities for students (Volet & Mansfield, 2006; Kimmel & Volet, 2012; Shaw, 2004). No solid conclusions or causal links can be established here, but responses are encouraging. Further, this suggests a continuation of the approaches derived from the ILF is merited.

A1 observed critical incidents suggesting that, for several students, reflecting on the learning experiences and utilising diversity as a means to improve learning, was challenging. This relates to dimensions five and six of the ILF, focusing on developing reflexive processes and fostering communities of learners (Arkoudis, et al., 2010, p. 6). For example, A1 recorded the following:

One group of students did not actively follow the reformation of groups, although they had recruited an individual who appeared to be a 'token' international student... At times they manipulated the ...activities... so that they did not have to mix with other students. ...they appeared to be aimed at alienating the student who was noticeably non-Caucasian...While students express an appreciation for the value of group work, without appropriate support and interventions, groups may become dysfunctional (Volet & Mansfield, 2006). In this unit, one group allowed itself to be dominated by a single student. A second group comprised of four very new international students and one domestic student, struggled to allocate tasks, and complete the assignment when the domestic student withdrew from the unit. Notable in both instances, and only evident on the evening of the group presentations, was the reluctance of the groups to seek early assistance. A system for early notification should be included in future group behavioural contracts. Despite the challenges encountered, students felt they developed skills which they may not have if they stayed within their own spheres.

Creating social connections

Responses to the question concerning contact with peers outside of class time were mixed. They ranged from only meeting for group assignment purposes to high levels of contact. Students cited lack of time as the reason for not mixing with their peers.

Yes I have contact outside the unit but only within the university. I did not go out with them but not because I did not like them. Everyone was just busy. We spoke about it.Quite a number of students indicated that while they did contact each other outside class time, this was often via email or social media, and mainly for their studies. One student observed:

For the group meeting we meet up weekly. I met up with one member of the group with regards to study and non-study... the whole team is more like friends towards the completion of the group work and we keep in touch via email and social network.For a few students, the group experience was ultimately very rewarding and they reported forming friendships. After this data was collected, students from this unit were observed working collaboratively on exam preparation. As they were no longer required to be working together, the continuation of intra-unit contact across cultures is encouraging.

The Kirkpatrick model offered a simple approach for explanation to diverse audiences, and was relatively easy to implement. It enabled advance preparation, and the development of simple structures to obtain data from students expeditiously, without diverting them from their learning. Similar to challenges experienced in the workplace (Kennedy, Chyung, Winiecki & Brinkerhoff, 2014), where evaluating the learning which has been transferred to other settings, and the return on expectations are difficult, educators need to consider the proxies which might be employed to ascertain level three and level four evaluations.

A comprehensive evaluation via a process of pre-post experimental design with a longitudinal perspective past the unit's conclusion would offer data suitable for a more in-depth analysis of the intervention. The Kirkpatrick model can be applied for this more complex evaluation with further thought and preparation. As with workplace evaluation, more complex approaches would require additional support and infrastructure (Kennedy, Chyung, Winiecki & Brinkerhoff, 2014), particularly for the level three and level four outcomes, Finally, it is important to recognise that the model would need to be adapted to suit the particular curriculum intervention being evaluated, and the circumstances in which the evaluation is taking place.

The application of the Kirkpatrick four level model in a single semester to a single cohort means that only moderatum generalisations can be offered (Williams, 2000). In subsequent semesters, modifications to some of the activities were made, based on student feedback, but the overall interactive format of classes was continued. These subsequent iterations were not subject to any ethics approval, and therefore are not reported here. In the semester under review, however, the Kirkpatrick four level model as a way of evaluating the application of the Interaction for Learning Framework has produced positive outcomes in a time efficient manner for both educators and students. Ongoing evaluation of the application of the Kirkpatrick model is recommended as the fit with other curriculum innovations is not fully known.

Alliger, G. M., Tannenbaum, S. I., Bennett, W., Traver, H. & Shotland, A. (1997). A meta-analysis of the relations among training criteria. Personnel Psychology, 50(2), 341-358. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1997.tb00911.x

Ameh, C. A. & van den Broek, N. (2015). Making it happen: Training health-care providers in emergency obstetric and newborn care. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 29(8), 1077-1091. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.03.019

Amoroso, L. M., Loyd, D. L. & Hoobler, J. M. (2010). The diversity education dilemma: Exposing status hierarchies without reinforcing them. Journal of Management Education, 34(6), 795-822. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1052562909348209

Arkoudis, S., Baik, C., Chang, S., Lang, I., Watty, K., Borland, H., Pearce, A. & Lang, J. (2010). Finding common ground: Enhancing interaction between domestic and international students. Centre for the Study of Higher Education, The University of Melbourne. http://www.cshe.unimelb.edu.au/research/experience/enhancing_interact.html

Arkoudis, S., Watty, K., Baik, C., Yu, X., Borland, H., Chang, S., Lang, I., Lang, J. & Pearce, A. (2013). Finding common ground: enhancing interaction between domestic and international students in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 18(3), 222-235. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2012.719156

Arthur, W., Tubre, T., Paul, D. S. & Edens, P. S. (2003). Teaching effectiveness: The relationship between reaction and learning evaluation criteria. Educational Psychology: An International Journal of Experimental Educational Psychology, 23(3), 275-285. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0144341032000060110

Australian Business Deans Council (2014). The future of management education: An initiative of the Australian Business Deans Council. Project Report, Deakin: ABDC. http://www.abdc.edu.au/pages/future-of-management-education.html

Bock, M. A. (2009). Impressionistic content analysis: Word counting in popular media. In K. Krippendorff & M. A. Bock (Eds.), The content analysis reader. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. pp. 38-42.

Bradley, D., Noonan, P., Nugent, H. & Scales, B. (2008). Review of Australian higher education: Final report. Canberra: Australian Government. https://www.mq.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0013/135310/bradley_review_of_australian_higher_education.pdf

Busch, D. (2009). What kind of intercultural competence will contribute to students' future job employability? Intercultural Education, 20(5), 429-438. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14675980903371290

Caruana, V. & Ploner, J. (2010). Internationalisation and equality and diversity in HE: Merging identities. Leeds: Equality Challenge Unit. http://www.ecu.ac.uk/publications/internationalisation-and-equality-and-diversity-in-he-merging-identities/

Chaney, M. (2013). Australia - educating globally. Canberra: International Education Advisory Council, Department of Industry, Innovation, Science, Research and Tertiary Education, Australian Government. http://apo.org.au/node/33223

Chang, N. & Chen, L. (2014). Evaluating the learning effectiveness of an online information literacy class based on the Kirkpatrick framework. Libri, 64(3), 211-223. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/libri-2014-0016

Collins, L. A., Smith, A. J. & Hannon, P. D. (2006). Applying a synergistic learning approach in entrepreneurship education. Management Learning, 37(3), 335-354. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1350507606067171

Denson, N. & Bowman, N. (2011). University diversity and preparation for a global society: The role of diversity in shaping intergroup attitudes and civic outcomes. Studies in Higher Education, 38(4), 555-570. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.584971

DeVita, G. (2007). Taking stock: an appraisal of the literature on internationalising HE learning. In E. Jones & S. Brown (Eds), Internationalising higher education. London: Routledge. 154-167.

Dyllick, T. (2015). Responsible management education for a sustainable world: The challenges for business schools. Journal of Management Development, 34(1), 16-33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JMD-02-2013-0022

Etherington, S. J. (2014). But science is international! Finding time and space to encourage intercultural learning in a content-driven physiology unit. Advances in Physiology Education, 38(2), 145-154. http://dx.doi.org/10.1152/advan.00133.2013

Green, W. & Whitsed, C. (2013). Reflections on an alternative approach to continuing professional learning for internationalization of the curriculum across disciplines. Journal of Studies in International Education, 17(2), 148-164. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1028315312463825

Green, W. & Whitsed, C. (Eds.) (2015). Critical perspectives on internationalising the curriculum in disciplines: Reflective narrative accounts from business, education and health. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Greene, J. C., Caracelli, V. J. & Graham, W. F. (1989). Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 11(3), 255-274. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/01623737011003255

Han, H. & Boulay, D. (2013). Reflections and future prospects for evaluation in human resource development. New Horizons in Adult Education and Human Resource Development, 25(2), 6-18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/nha.20013

Harrison, N. (2015). Practice, problems and power in 'internationalisation at home': Critical reflections on recent research evidence. Teaching in Higher Education, 20(4), 412-430. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2015.1022147

Harrison, N. & Peacock, N. (2010). Cultural distance, mindfulness and passive xenophobia: Using integrated threat theory to explore home higher education students' perspectives on 'internationalisation at home'. British Educational Research Journal, 36(6), 877-902. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01411920903191047

Ho, A. D. D., Arendt, S. W., Zheng, T. & Hanisch, K. A. (2016). Exploration of hotel managers' training evaluation practices and perceptions utilizing Kirkpatrick's and Phillips's models. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 15(2), 184-208. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15332845.2016.1084861

Holton, E. F. (1996). The flawed four-level evaluation model. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 7(1), 5-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.3920070103

Kennedy, P. E., Chyung, S. Y., Winiecki, D. J. & Brinkerhoff, R. O. (2014). Training professionals' usage and understanding of Kirkpatrick's level 3 and level 4 evaluations. International Journal of Training and Development, 18, 1-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ijtd.12023

Kimmel, K. & Volet, S. (2012). University students' perceptions of and attitudes towards culturally diverse group work. Does context matter? Journal of Studies in International Education, 16(2) 157-181. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1028315310373833

Kirkpatrick, J. & Kayser-Kirkpatrick,W. (2014). The Kirkpatrick four levels: A fresh look after 55 years. Ocean City: Kirkpatrick Partners.

Leask, B. (2008). Internationalisation, globalisation and curriculum innovation. In M. Hellstén & A. Reid. (Eds), Researching international pedagogies: Sustainable practice for teaching and learning in higher education. Dordrecht: Springer. pp.9-26.

Leask, B. (2009). Using formal and informal curricula to improve interactions between home and international students. Journal of Studies in International Education, 13(2), 205-221. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1028315308329786

Leask, B. & Beelen, J. (2009). Enhancing the engagement of academic staff in international education. In Proceedings of a joint IEAA-EAIE Symposium: Advancing Australia-Europe Engagement. Sydney: University of New South Wales. pp.1-16. http://www.ieaa.org.au/documents/item/41

Leask, B. & Carroll, J. (2011). Moving beyond 'wishing and hoping': Internationalisation and student experiences of inclusion and engagement. Higher Education Research & Development, 30(5), 647-659. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2011.598454

Mak, A. S. & Kennedy, M. (2012). Internationalising the student experience: Preparing instructors to embed intercultural skills in the curriculum. Innovative Higher Education, 37(4), 323-334. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10755-012-9213-4

Mintzberg, H. & Gosling, J. (2002). Educating managers beyond borders. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 1(1), 64-76. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/AMLE.2002.7373654

Osmond, J. & Roed, J. (2010). Sometimes it means more work...: Student perceptions of group work in a mixed cultural setting. In E. Jones (Ed), Internationalisation and the student voice: Higher education perspectives. New York: Routledge. pp.113-124.

Paull, M. (2015). 'Yes! That means getting out of your seat': Interactive learning strategies for internationalising the curriculum in post graduate business education in an Australian university. In W. Green and C. Whitsed (Eds), Critical perspectives on internationalising the curriculum in disciplines: Reflective narrative accounts from business, education and health. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Praslova, L. (2010). Adaptation of Kirkpatrick's four level model of training criteria to assessment of learning outcomes and program evaluation in higher education. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 22(3), 215-225. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11092-010-9098-7

Prescott, A. & Hellstén, M. (2005). Hanging together with non-native speakers: The international student transition experience. In P. Ninnes & M. Hellstén (Eds.), Internationalizing higher education: Critical explorations of pedagogy and practice (pp. 75-95). Hong Kong: Comparative Education Research Centre, Springer.

Randolph, W. A. (2011). Developing global business capabilities in MBA Students. Journal of Management Inquiry, 20(3), 223-240. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1056492611401027

Rogers, R. R. (2001). Reflection in higher education: A concept analysis. Innovative Higher Education, 26(1), 37-57. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1010986404527

Saks, A. M. & Haccoun, R. R. (2010). Managing performance through training and development. Toronto: Nelson.

Schlegelmilch, B. B. & Thomas, H. (2011). The MBA in 2020: Will there still be one? The Journal of Management Development, 30(5), 474-482. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02621711111132984

Schullery, N. M. & Schullery, S. E. (2006). Are heterogeneous or homogeneous groups more beneficial to students? Journal of Management Education, 30(4), 542-556. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1052562905277305

Shaw, J. B. (2004). A fair go for all? The impact of intragroup diversity and diversity-management skills on student experiences and outcomes in team-based class projects. Journal of Management Education, 28(2), 139-169. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1052562903252514

Spencer-Oatey, H. & Dauber, D. (2016). The gains and pains of mixed national group work at university. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1-18. [online ahead of print]. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2015.1134549

Steele, L. M., Mulhearn, T. J., Medeiros, K. E., Watts, L. L., Connelly, S. & Mumford, M. D. (2016). How do we know what works? A review and critique of current practices in ethics training evaluation. Accountability in Research, [online ahead of print]. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2016.1186547

Taras, V., Caprar, D. V., Rottig, D., Sarala, R. M., Zakaria, N., Zhao, F., Jiminez, A. et al. (2013). A global classroom? Evaluating the effectiveness of global virtual collaboration as a teaching tool in management education. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 12(3), 414-435. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/amle.2012.0195

Volet, S. & Mansfield, C. (2006). Group work at university: Significance of personal goals in the regulation strategies of students with positive and negative appraisals. Higher Education Research & Development, 25(4), 341-356. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07294360600947301

Wamboye, E., Adekola, A. & Sergi, B. S. (2015). Internationalisation of the campus and curriculum: Evidence from the US institutions of higher learning. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 37(4), 385-399. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2015.1056603

Whitsed, C. (2010). Internationalising your unit: Case studies from Murdoch. Centre for University Teaching and Learning, Murdoch University. Accessed 12/06/24 from http://our.murdoch.edu.au/Educational-Development/Preparing-to-teach/Internationalising-your-unit/

Williams, M. (2000). Interpretivism and generalisation. Sociology, 34(2), 209-224. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/S0038038500000146

Yardley, S. & Dornan, T. (2012). Kirkpatrick's levels and education 'evidence'. Medical Education, 46(1), 97-106. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04076.x

Acknowledgement: This is a revised and expanded version of a paper presented at TL Forum 2016:

Paull, M., Whitsed, C. & Girardi, A. (2016). Applying the Kirkpatrick model: Evaluating Interaction for Learning Framework curriculum interventions. In Purveyors of fine learning since 1992. Proceedings of the 25th Annual Teaching Learning Forum, 28-29 January 2016. Perth: Curtin University. http://ctl.curtin.edu.au/events/conferences/tlf/tlf2016/refereed/paull.pdfAuthors: Dr Megan Paull in the Centre for Responsible Citizenship and Sustainability, School of Business and Governance at Murdoch University has a strong interest in sound pedagogy and student engagement in learning, with interaction between students being a primary focus of her educational strategies. Megan's research interests extend beyond teaching scholarship to areas related to volunteering and nonprofit organisations, and organisational behaviour. Email: m.paull@murdoch.edu.au Web: http://profiles.murdoch.edu.au/myprofile/megan-paull/ Dr Craig Whitsed in the Centre for University Teaching and Learning at Murdoch University teaches across a range of learning contexts and modes including academic professional development and training; postgraduate and undergraduate teaching; and HDR supervision. His primary research focus is in the area of Internationalisation of the Curriculum in Higher Education. Email: c.whitsed@murdoch.edu.au Web: http://profiles.murdoch.edu.au/myprofile/craig-whitsed/ Associate Professor Antonia Girardi in the School of Business and Governance at Murdoch University teaches in the areas of research methods and human resources management. In 2015, she was a recipient of the Murdoch University Vice Chancellor's Award for Excellence in Learning and Teaching for her work on building student self-efficacy beliefs through the creation of a holding environment. Email: a.girardi@murdoch.edu.au Web: http://profiles.murdoch.edu.au/myprofile/antonia-girardi/ Please cite as: Paull, M., Whitsed, C. & Girardi, A. (2016). Applying the Kirkpatrick model: Evaluating an Interaction for Learning Framework curriculum intervention. Issues in Educational Research, 26(3), 490-507. http://www.iier.org.au/iier26/paull.html |