|

Teaching teamwork in Australian university business disciplines: Evidence from a systematic literature review

Linda Riebe

Edith Cowan University, Australia

Antonia Girardi and Craig Whitsed

Murdoch University, Australia

Australian employers continue to indicate that the development of teamwork skills in graduates is as important as mastering technical skills required for a particular career. In Australia, the reporting on the teaching of teamwork skills has emanated across a range of disciplines including health and engineering, with less of a focus on business related disciplines. Although Australian university business schools appear to value the importance and relevance of developing teamwork skills, implementation of the teaching, learning, and assessment of teamwork skills remains somewhat of a pedagogical conundrum. This paper presents evidence from a systematic literature review as to the salient issues associated with teaching teamwork skills in Australian university business disciplines.

Much of the research focusing on the teaching of teamwork skills in higher education has emanated from the United States (see Riebe, Girardi & Whitsed, 2016 for a recent review). Within the Australian context, the reporting on the teaching of teamwork skills, while less prevalent, is presented across a range of disciplines including health and engineering, with less of a focus on business related fields. This limited focus across business disciplines is surprising given the attention of educators/researchers on ensuring compliance with teaching standards requiring general skills development in curriculum content. For those university business schools maintaining or aspiring to AACSB (Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business, n.d.) accreditation, in particular, there is an expectation that teamwork skills will be developed and include learning experiences that address this expectation, along with technical knowledge in business degree programs.

Given the increased focus on accreditation compliance expectations, and calls from employers to improve the skills, knowledge, and behaviours associated with teamwork, the development of teamwork skills (broadly defined) in Australian university business disciplines merits further investigation. This research forms part of a larger study investigating how teamwork is taught, practiced and assessed in university business courses in culturally similar countries.

In this paper, we pose the question: What are the salient issues associated with teaching teamwork skills in Australian university business disciplines evident in the literature? We define teamwork as two or more students formally working together toward a common goal through interdependent behaviour and personal accountability. Although we use the terms 'team' and 'teamwork', we acknowledge that others use the terms 'group' and 'group work' when discussing student teams. These terms are often used interchangeably; however, not all groups are teams. Groups can be any subset of people with similar traits, characteristics, culture or interests, whereas teams are usually formed to work interdependently to complete a short-term project, driven by a common goal (Kirby, 2011). To maintain the integrity of the original research when cited, we have used both terms. We conducted a systematic literature review to present an overview of recent literature emanating from Australia on teamwork teaching and learning issues in university business disciplines.

In selecting the literature, the following inclusion criteria were observed. The articles must:

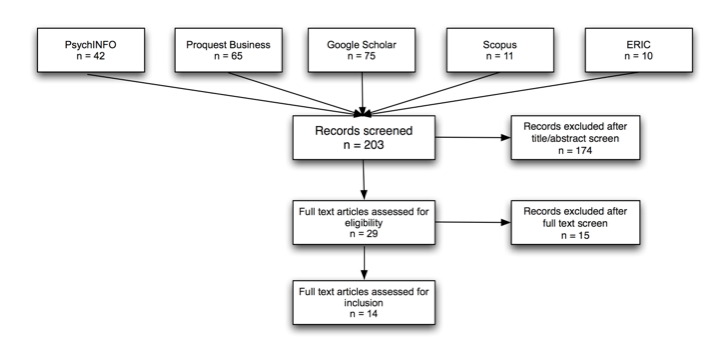

Figure 1: Flowchart of the literature selection process

As recommended by Pickering and Byrne (2014), articles found in the initial search were screened and then placed in an Excel database with the following headings: authors' name(s); year of publication; title of the article; journal title; research design (including sample information); geography (according to authors university affiliation); theme; and, findings. The database allowed for the filtering of article information into the various headings. The first filter removed all non-Australian university affiliated authors. Full-text articles (n = 29) were then filtered by the relevant inclusion criteria noted for the study, leaving 14 journal articles by Australian university affiliated authors. Table 1 identifies the articles selected for the systematic review. Coding of the 14 articles was conducted in preparation for the analysis. Each article was allocated a number used to identify the article in the following sections.

| No. | Author(s) (Year) | Article title | Research design/ Size/Discipline | Content |

| 1 | Burdett & Hastie (2009) | Predicting satisfaction with group work assignments | Mixed method/ n = 344 undergrad final year business students | Pedagogy/ Student perceptions |

| 2 | Chad (2012) | The use of team-based learning as an approach to increased engagement and learning for marketing students | Case study/ n = 50 postgraduate final year marketing students | Pedagogy |

| 3 | D'Alessandro & Volet (2012) | Balancing work with study: Impact on marketing students experience of group work | Quantitative/ n = 222 undergrad marketing students | Pedagogy/ Student perceptions |

| 4 | Delaney, Fletcher, Cameron & Bodle (2013) | Online self and peer assessment of teamwork in accounting education | Mixed method/ n = 93 second year undergrad accounting students | Assessment/ Student perceptions |

| 5 | Freeman (2012) | To adopt or not to adopt an innovation: A case study of team-based learning | Qualitative | Pedagogy/ Educator perceptions |

| 6 | Hunter, Vickery & Smyth (2010) | Enhancing learning outcomes through group work in an internationalized undergraduate business education context | Action research/ focus groups, business undergrad students: Time 1 n = 108; Time 2 n = 28 | Pedagogy/ Student perceptions and educator diary reflections |

| 7 | Jackling, Natoli, Siddique & Sciulli (2014) | Student attitudes to blogs: a case study of reflective and collaborative learning | Quantitative/ n = 111 2nd year undergrad accounting students | Assessment/ Student perceptions |

| 8 | Jackson, Sibson & Riebe (2013) | Undergraduate perceptions of the development of team-working skills | Mixed method/ n = 799 undergrad business students | Pedagogy/ Student perceptions |

| 9 | Lambert, Carter & Lightbody (2014) | Taking the guesswork out of assessing individual contributions to group work assignments | Qualitative/ n = 232 postgrad. and n = 325 undergraduate accounting students | Assessment/ Educator perspective |

| 10 | Riebe, Roepen, Santarelli & Marchioro (2010) | Teamwork: Effectively teaching an employability skill | Qualitative/ n = 160 second year undergrad business students | Pedagogy/ Case study |

| 11 | Sargent, Allen, Frahm & Morris (2009) | Enhancing the experience of student teams in large classes | Mixed method/ Control n = 101 Experimental n = 564 | Pedagogy |

| 12 | Seethamraju & Borman (2009) | Influence of group formation choices on academic performance | Mixed method/ n = 141 postgrad business info. systems students | Pedagogy |

| 13 | Teo, Segal, Morgan, Kandlbinder, Wang & Hingorani (2012) | Generic skills development and satisfaction with group work among business students | Quantitative/ n = 389 postgrad and undergrad students | Pedagogy/ Student perceptions |

| 14 | Troth, Jordan & Lawrence (2012) | Emotional intelligence, communication competence, and student perceptions of team social cohesion | Quantitative/ Final sample n = 273 university business students | Pedagogy |

| WA | SA | VIC | NSW | QLD | TAS | ACT | NT | Other | Totals | |

| No of articles | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 14 |

| No of universities* | 5 | 3 | 9 | 11 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 39 |

| Notes: WA = Western Australia; SA = South Australia; VIC = Victoria; NSW = New South Wales; QLD = Queensland; TAS = Tasmania; ACT = Australian Capital Territory; NT = Northern Territory. *Number of universities based on 2014 figures. | ||||||||||

| Content | Methods | Totals | |||

| Quantitative | Qualitative | Mixed method | Other | ||

| Pedagogy | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 11 |

| Assessment | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Totals | 4 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 14 |

Quantitative approaches were used in four articles (3, 7, 13, 14); and three articles used a qualitative approach (5, 9, 10). The mixed method approach was favoured slightly more than others, with five articles (1, 4, 8, 11, 12) using this method. Mixed method studies were defined as those studies which included "both types of data sources and both forms of analysis, whether performed simultaneously or sequentially as part of an a priori design or an adaptive, evolutionary process" (Truscott et al., 2010, p. 318). Two of the articles are noted as other - one (article 2) adopted a case study approach and one (article 6) used an action research approach.

| Theme | Variables | Mentioned in article(s) |

| Team formation and management | Team formation | 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 14 |

| Team cohesion | 6, 12, 14 | |

| Teaching and learning approach | Teaching and learning strategies/processes | 6, 9, 10, 11,14 |

| Constructive alignment | 4, 6, 8, 10 | |

| Assessment/marks/grading | 1, 4, 7, 9, 13, 14 | |

| Active/collaborative/student-centred learning | 5, 8 | |

| Team-based learning | 2, 5 | |

| Challenges affecting teaching and learning practices | Cultural diversity/mix | 5, 6, 13 |

| Workload | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 13 | |

| Assessment/marks/grading | 1, 4, 7, 9, 13, 14 |

Team formation and management

Half of the articles focused on team formation and team management issues. Team formation and composition of teams are somewhat contentious issues for both students and educators in terms of size and the way in which teams are structured and supported. This is not a new issue in higher education, nor in fact in the workplace, as team composition inherently includes complications arising from individualistic and/or collectivist cultural understandings, communication and decision-making styles (Gibson & Saxton, 2005). This aspect can be considered closely related to issues of homogeneity/ heterogeneity, where people tend to prefer to work with others more like themselves as observed by Volet and Ang (1998). Where the size of teams was mentioned in the articles, a team size of between three and five members was recommended.

Reflecting on the challenges of team formation and management, three contesting orientations to this were observed. Some researchers (e.g. Hunter, Vickery & Smyth, 2010; Jackson et al., 2014; Troth, Jordan & Lawrence, 2012) advocated for educator allocation of students to teams to promote diversity of culture, gender, age, team role profiles and, the level of emotional intelligence. While Seethamjura and Borman's (2009) research with postgraduate students suggested that heterogeneity of team members contributes to team success, they concluded that students should self-select team membership. The findings of Jackling, Natoli, Siddique and Sciulli (2014) suggested that team composition has a significant impact on student perceptions of group work. For example, the research by Jackling et al., (2014) was based on student self-selected dyads, with the rationale for the smaller team size being to mitigate anxiety associated with lecturer formed teams. However, they acknowledged that self-selecting into teams is not generally reflective of real-world situations and that findings may not be transferable to larger groups. Alternatively, Sykes, Moerman, Gibbons and Dean (2014) argued that the notion of real-world teamwork in the university classroom is clichˇd and "chimera-like in the student experience" (p. 11). What this suggests is that research on the formation and composition of teams and teamwork in the university context continues to be debated, with arguments both for and against self-selection evident in the literature.

There is also evidence in the literature reviewed that Australian researchers are concerned with team cohesion. Hunter et al. (2010) posited that meetings between educators and individual teams to discuss issues assist with the development of team cohesion. Such an argument finds support in the workplace, where external third parties are known to be contracted by organisations to provide input on team goal clarification and to improve team effectiveness by keeping teams on track with strategic priorities (Gibson & Saxton, 2005). Troth et al. (2012) discussed the implications of emotional intelligence training as a way of improving team social cohesion. They further suggest that emotional intelligence could be a factor in determining the allocation of students to teams. While Seethamjura and Borman (2009) found that how a team is formed ultimately influences the team's performance, they also implicated social cohesion as a latent variable and an important factor in the construct of teams. In general, the research suggests that there is potential for a team to perform better where there is social cohesion. This implies that the inclusion of innovative teaching and learning approaches to establish team cohesion and social dynamics, such as emotional intelligence training, would benefit both university students and educators in the management of student teams.

Teaching and learning approaches

Specific innovative pedagogical approaches were noted in three articles in this review. For example, team-based learning was presented in two articles (Chad, 2012; Freeman, 2012). Team-based learning includes four elements: strategically formed teams; a readiness assurance process - questions initially undertaken by individuals and then followed up with the team through a consensus decision-making process, peer evaluation, and small group activities. Freeman's (2012) article provided a description of the team-based learning phases of readiness, application, and assessment, and investigated team-based learning adoption in a research-intensive Australian university. It is apparent in both articles that although the introduction of team-based learning offered students an enhanced team learning experience, it also added to the workload commitment of the academic adopter. Reinig, Horowitz and Whittenburg's (2011) research indicated student satisfaction with the team-based learning readiness assurance process "in the attainment of multiple goals" (p. 44); however, they noted that relationships between social dynamics and student satisfaction were not examined. Another innovative approach to teamwork teaching and learning was outlined by Sargent, Allen, Frahm and Morris (2009) in their strategy to develop team coaching skills in teaching assistants by providing the assistants with training in coaching and feedback skills to student teams in a large management course. The findings of their study indicated that the outcome of this applied process approach was a positive experience for student teams and teaching assistants. This outcome implied that the trade-offs between positive student experience and educator workload is an issue influencing the adoption of innovative pedagogical approaches, and must be acknowledged and supported at the institutional level.

The design of team assessments is a factor that is of concern to university educators, particularly in how to address individual grading of team members (Lambert, Carter & Lightbody, 2014), and in the use of self and/or peer assessment. In the articles, peer assessment is presented most often as a strategy to ensure accountability of individual team members (D'Alessandro & Volet, 2012; Delaney et al., 2013), discourage social loafing and non-cooperation (Burdett & Hastie, 2009), and increase distributive justice. For example, Burdett and Hastie (2009) suggested interventions to overcome student perceptions of inequity of workload distribution by providing a mechanism to adjust individual team member grades. They elaborated the importance of distributive and procedural justice as predictors of students' commitment, persistence, and satisfaction with group work. Other strategies for applying grading mechanisms, including a self and peer assessment model through the implementation of the online tool, SPARKPLUS (Self and Peer Assessment Resource Kit), were outlined by Delaney et al. (2013). By contrast, Lambert et al. (2014) placed less reliance on peer evaluation as a strategy to deal with individual accountability and instead, argued for team member accountability through contributions to a team wiki. Wikis, often available through the university learning management system, allow educators to textually track individual contributions of individual team members. However, there are drawbacks to wiki use for this purpose as some wikis only record the name and date of the last contributor. Therefore, contributions to the wiki must be notated in some way or, for example, colour coded to indicate an individual student's contribution. Riebe et al. (2010) also advocated for the use of a team wiki to promote individual team member accountability, but also implemented peer evaluation processes as formative checkpoints in team projects.

Constructive alignment (Biggs, 1999) of assessments and activities with intended learning outcomes was mentioned as the basis from which to ensure team-working skill development (Delaney et al., 2013; Jackson et al., 2014; Riebe et al., 2010). Riebe et al. (2010) proposed that constructive alignment supports students' understanding of the development of behaviours associated with the process of teamwork. Jackson et al. (2014) argued that educators must "explicitly articulate the connections between the constructive alignment of the unit's activities and assessments with the learning outcomes" (p. 15), so that students are able to self-report on the outcome of the development of teamwork skills. Such an approach is not common in the extant literature; however, it is an area of teaching and learning that is worthy of further research, especially given the evidence requirements of professional accreditation bodies (Delaney et al., 2013) of the development of teamwork skills during an undergraduate degree. In Australia, the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) has specified standards which require achievement of not only core discipline skills, but also for "...generic, employment-related and lifelong learning" (TEQSA, 2016, p. 2), such as teamwork skills. The AACSB also set standards that require "learning methods that actively involve students in the learning process [and] encourage collaboration..." (Reinig et al., 2011, p. 28) developed through teamwork. It is, therefore, important for universities to articulate alignment of content and assessments to ensure that both discipline knowledge and generic, employment-related skills (such as teamwork) are incorporated into course design.

Challenges affecting teaching and learning practices

The influence of organisational culture on teaching practices in universities, as well as the cultural background of university business students, was mentioned in the literature reviewed as influencing teamwork pedagogy. For example, Freeman (2012) referred to a change in teaching culture requiring educators to move from a lecture-based pedagogy to one of active learning. Such external forces are seen to contribute to resistance to change or resentment among academics. Freeman explained, "some academics may resent the extra investment of time and effort required of them in implementing change or they may prefer to transmit information through traditional lectures and tutorials" (2012, p. 157). Implementation of active and collaborative learning methods is supported in the literature as high-impact pedagogical practices that benefit student success, particularly for underserved students who are less likely to have access to these practices (Kemery & Stickney, 2014; Kuh, 2008). As an example, Hunter et al., (2010) outlined the need for time to develop cultural sensitivity so that undergraduate students learn to cope with group diversity through proactive teaching and learning strategies. Teo, Segal, Morgan, Kandlbinder, Wang and Hingorani (2012) concurred, stating that "developing intercultural competence in students and academics is a clear priority" (p. 482) in the development of teamwork skills.

Workload and assessment practices were also discussed as impacting student satisfaction with teamwork. Workload sharing is noted as a burden for students, with a variety of viewpoints raised by researchers (Chad, 2012; Hunter et al., 2010; Troth et al., 2012). Social loafing is where one or more team members do not contribute their fair share, causing additional workload for others. Social loafing (also known as free-riding) has been well-documented as a discouraging aspect of university student teamwork in the extant literature (see for example Jassawalla, Sashittal & Malshe, 2009; Kouliavstev, 2012; Maiden & Perry, 2011; Pieterse & Thompson, 2010). D'Alessandro and Volet (2012) discussed the impact that external part-time work hours has on student attitudes to group work at university, finding that "student learning in groups is adversely affected by substantial hours of part-time employment" (p. 103). While workload issues have focused mainly on student perspectives, one must also consider educator workload. A study by Sashittal, Jassawalla and Markulis (2011) found that undergraduate business students still do not receive adequate training and instruction in teamwork skills prior to being assigned large, multi-outcome team projects. Planning and implementing team training for students, on top of normal content planning, is an additional workload for educators. Further, by necessity, the educators must train themselves, or seek access to professional development (Albon & Jewels, 2014), in collaborative learning techniques in order to both plan and model the collaborative skills underlying team working. The role of the institution in facilitating this focus on professional development for educators and how this impacts the uptake of teaching teamwork skills merits further attention.

There are many challenges faced by educators and students that affect the teaching and learning of teamwork skills in university business disciplines evident in the extant literature. One particularly prevalent challenge is dealing with social loafers in teams. Less prevalent in the literature reviewed is research around the processes of teamwork pedagogy and, the investigation of cultural factors that may affect student teams. The latter may be because educators are not as focused on cultural aspects, which would be surprising given that Australian universities host many international students in business courses. It may also be because educators are already dealing with a crowded discipline-specific curriculum and, although aware of the importance of addressing team processes and cultural differences in business classes, do not have the time to teach these aspects formally. Research that explores these rationales is necessary. The role of institutional practices in affording educators the opportunity to engage in activities which further promote opportunities to teach teamwork skills is also a significant consideration warranting further research.

In order to understand how teamwork is situated as a learned employability skill in business related disciplines in the Australian university context, consideration was given to common themes arising across the literature reviewed. The 14 articles have suggested or operationalised certain approaches to deal with specific concerns linked to teamwork pedagogy and assessment practices. For example, the use of team-based learning has been implemented to enhance and improve student engagement with teamwork (Chad, 2012). Student perceptions of (dis)satisfaction with teamwork assessment have been attributed to considerations of social loafing, workload of individual team members (both within the university environment and in relation to external employment hours undertaken by students), and the distributive justice related to grading team assignments. Concerns about teamwork assessment practices were also highlighted across articles reviewed (see for example Burdett & Hastie, 2009; Delaney et al., 2013; Lambert et al., 2014).

Three themes were identified across the literature reviewed: team formation and management; teaching and learning approaches; and, challenges influencing teaching and learning practices. Remarkably, little attention has been paid to training students in the processes of teamwork. There are numerous factors that potentially contribute to this. For example, university educators, dealing with the competing interests of teaching an already crowded curriculum, or a change in teaching culture to focus on development and assessment of process skills, may be deterred from adopting a process over product approach to teaching teamwork. Further research that explores factors that influence educators' rationales relating to the inclusion or exclusion of explicit teamwork training and how this is integrated into programs of study at the course and unit level is warranted.

Moreover, and related to curriculum design, is the need for research that explores how and in what ways educators understand and construe their curriculum and learning design approaches. Biggs' (1999) constructive alignment approach, for example, could assist in the design of program activities to better ensure teamwork skill development outcomes are articulated (see also Trigwell & Prosser, 2014). The review also challenged the assumption that academics in business related disciplines require less professional development support as this relates to teamwork pedagogy and learning design. Research that explores the perspective that business academics, being discipline-based scholars, may not have adequate training in pedagogical practices or curriculum design principles (Albon & Jewels, 2014) is necessitated, given the limited focused attention on this dimension in the articles reviewed.

Contributing to the need for further research is the contested terminology and the multi-vocalness of teamwork and related synonyms and rationales underpinning the incorporation of teamwork into a course as a learning or assessment task. For example, when group projects are introduced as a synonym for the use of teamwork, or to reduce educator marking load, training students to develop the process skills of teamwork may be overlooked, which has the potential to negatively influence the student learning experience and educational outcomes. Providing training resources to educators was identified as a way to improve academics' understanding of pedagogical strategies associated with professional learning (Freeman, 2012). A lack of resources may inhibit the ability of universities to respond to the changing needs of employers, and hence, the redesign of curricula to incorporate skill development in courses in budgetary constrained environments. The type of institutional support needed for academics to teach teamwork skills is an area in need of further exploration.

This review has also identified phenomena that have a significant influence on university students' satisfaction and motivation to engage in teamwork, team learning tasks, and assessments. The broader literature identifies many factors for consideration, which has the potential to inform new and innovative ways to engage students in teamwork related learning. Extrinsic motivation has been widely linked to student motivation. For example, students are motivated primarily by assessment (Ramsden, 1992) and therefore, when it comes to developing teamwork skills, curriculum design that incorporates both process and product outcomes in the assessment may engage students with deep learning (Delaney et al., 2013). Yet, this approach amplifies the transactional dimension of this form of learning approach and elevates it to a high stakes form of assessment and learning experience, where marks are often linked to performance of group members, rather than the individual, thereby intensifying students' negative perceptions associated with assessment marks and grading (Burdett & Hastie, 2009).

In particular, individual grades being affected by the multicultural nature of teamwork at university (Teo et al., 2012; Volet & Ang, 1998), and fears associated with social loafing of peers in team assessments were noted. While these are well-defined problems as they relate to assessment, further research exploring how best to structure teamwork learning tasks that are perceived as equitable, while ensuring assessments and learning are aligned within the university context, is needed. Further, to the issue of perceptions of the equitable distribution of work, students' external employment commitments were identified as a negative influence on student perceptions of fairness in teamwork assessment. For example, D'Alessandro and Volet (2012) reported on the effect of external part-time employment negatively impacting student appraisals of teamwork experiences more than teams where team members did not have high levels of external commitments. Finally, it was observed that explicitly teaching teamwork skills at university also has implications for educator workload. Introducing innovative teamwork strategies and collaborative pedagogy incurs additional time and effort on the part of educators to implement change, with implications for universities to recognise this as part of their workload management strategy.

Research employing a systematic literature review methodology has the potential to highlight as yet unexplored gaps, and present a platform from which future research agendas can be developed. This review has provided a way of interrogating the literature that is less subjective than traditional reviews. In the time since the initial literature search and review was conducted, several articles related to teamwork teaching and learning in the Australian university business context have been published (see for example, Augar, Woodley, Whitefield & Winchester, 2016; Betta, 2016; Volkov & Volkov, 2015), further supporting the need for further research on the teaching of teamwork skills and unpacking the factors that influence this across Australian universities. Though limited in scope, the systematic literature review presented here has highlighted emergent themes and future research foci which must take into consideration how individual student, educator, and institutional factors interact to influence the teaching of teamwork skills in Australian universities.

Albon, R. & Jewels, T. (2014). Mutual performance monitoring: Elaborating the development of a team learning theory. Group Decision and Negotiation, 23(1), 149-164. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10726-012-9311-9

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business [AACSB] (n.d.). 2013 Business accreditation standards. http://www.aacsb.edu/accreditation/standards/2013-business

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business [AACSB] (2016). AACSB-accredited schools worldwide. http://www.aacsb.edu/accreditation/accredited-members

Augar, N., Woodley, C., Whitefield, D. & Winchester, M. (2016). Exploring academics' approaches to managing team assessment. The International Journal of Educational Management, 30(6), 1150-1162. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-06-2015-0087

Australian Association of Graduate Employers [AAGE] (2012). AAGE employer survey: Survey report. Melbourne, Australia: High Flyers Research.

Australian Association of Graduate Employers [AAGE]. (2014). AAGE Employer survey: Survey report. Melbourne, Australia: High Flyers Research.

Australian Industry Group and Deloitte (2009). National CEO survey - Skilling business in tough times. North Sydney, Australia: The Australian Industry Group. http://pandora.nla.gov.au/pan/124898/20110203-1059/www.aigroup.com.au/portal/binary/com.

epicentric.contentmanagement.servlet.ContentDeliveryServlet/LIVE_CONTENT/Publications/Reports/2009/

7956_Skilling_business_in_tough_times_FINAL.pdf

Bennett, R. (2002). Employers' demands for personal transferable skills in graduates: A content analysis of 1000 job advertisements and an associated empirical study. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 54(4), 457-476. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13636820200200209

Betta, M. (2016). Self and others in team-based learning: Acquiring teamwork skills for business. Journal of Education for Business, 91(2), 69-74. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2015.1122562

Biggs, J. (1999). What the student does: Teaching for enhanced learning. Higher Education Research & Development, 18(1), 57-75. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0729436990180105

Briner, R. & Denyer, D. (2012). Systematic review and evidence synthesis as a practice and scholarship tool. In D. M. Rousseau (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of evidence-based management (pp. 112-129). New York: Oxford University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199763986.013.0007

*Burdett, J. & Hastie, B. (2009). Predicting satisfaction with group work assignments. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 6(1), 61-71. http://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1077&context=jutlp

*Chad, P. (2012). The use of team-based learning as an approach to increased engagement and learning for marketing students: A case study. Journal of Marketing Education, 34(2), 128-139. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0273475312450388

*D'Alessandro, S., & Volet, S. (2012). Balancing work with study: Impact on marketing students' experience of group work. Journal of Marketing Education, 34(1), 96-107. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0273475311432115

*Delaney, D., Fletcher, M., Cameron, C. & Bodle, K. (2013). Online self and peer assessment of team work in accounting education. Accounting Research Journal, 26(3), 222-238. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/ARJ-04-2012-0029

*Freeman, M. (2012). To adopt or not to adopt an innovation: A case study of team-based learning. International Journal of Management Education, 10(3), 155-168. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2012.06.002

Gibson, C. B. & Saxton, T. (2005). Thinking outside the black box: Outcomes of team decisions with third-party intervention. Small Group Research, 36(2), 208-236. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1046496404270376

Harder, C., Jackson, G. & Lane, J. (2014). Talent is not enough: Closing the skills gap. Canada West Foundation. http://cwf.ca/research/publications/talent-is-not-enough-closing-the-skills-gap/

*Hunter, J., Vickery, J. & Smyth, R. (2010). Enhancing learning outcomes through group work in an internationalised undergraduate business education context. Journal of Management and Organization, 16(5), 700-714. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1833367200001814

*Jackling, B., Natoli, R., Siddique, S. & Sciulli, N. (2014). Student attitudes to blogs: A case study of reflective and collaborative learning. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 40(4), 542-556. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2014.931926

*Jackson, D., Sibson, R. & Riebe, L. (2014). Undergraduate perceptions of the development of team-working skills. Education + Training, 56(1), 7-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/ET-01-2013-0002

Jassawalla, A., Sashittal, H. & Malshe, A. (2009). Students perceptions of social loafing: Its antecedents and consequences in undergraduate business classroom teams. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 8(1), 42-54. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/amle.2009.37012178

Kemery, E. R. & Stickney, L. T. (2014). A multifaceted approach to teamwork assessment in an undergraduate program. Journal of Management Education, 38(3), 462-479. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1052562913504762

Kirby, D. (2011). No-one can whistle a symphony. It takes an orchestra to play it. Asian Social Science, 7(4), 36-43. http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ass.v7n4p36

Kouliavtsev, M. (2012). Social loafers, free-riders, or diligent isolates: Self-perceptions in teamwork. Atlantic Economic Journal, 40(4), 437-438. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11293-012-9333-3

Kuh, G. D. (2008). High-impact educational practices: What they are, who has access to them, and why they matter. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities. https://www.aacu.org/leap/hips

*Lambert, S., Carter, A. & Lightbody, M. (2014). Taking the guesswork out of assessing individual contributions to group work. Issues in Accounting Education, 29(1), 169-180. http://dx.doi.org/10.2308/iace-50637

Maiden, B. & Perry, B. (2011). Dealing with free riders in assessed group work: Results from a study at a UK university. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 36(4), 451-464. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602930903429302

Pickering, C. & Byrne, J. (2014). The benefits of publishing quantitative systematic literature review for PhD candidates and other early career researchers. Higher Education Research & Development, 33(3), 534-548. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2013.841651

Pieterse, V. & Thompson, L. (2010). Academic alignment to reduce the presence of social loafers and 'diligent isolates' in student teams. Teaching in Higher Education, 15(4), 355-367. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2010.493346

Ramsden, P. (1992). Learning to teach in higher education. London, England: Routledge.

Reinig, B., Horowitz, I. & Whittenburg, G. (2011). The effect of team-based learning on student attitudes and satisfaction. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 9(1), 27-47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4609.2010.00289.x

Riebe, L., Girardi, A. & Whitsed, C. (2016). A systematic literature review of teamwork pedagogy in higher education. Small Group Research, 47(6), 619-664. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1046496416665221

*Riebe, L., Roepen, D., Santarelli, B. & Marchioro, G. (2010). Teamwork: Effectively teaching an employability skill. Education + Training, 52(6/7), 528-539. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00400911011068478

Rousseau, D., Manning, J. & Denyer, D. (2008). Evidence in management and organizational science: Assembling the field's full weight of scientific knowledge through syntheses. Annals of the Academy of Management, 2(1), 475-515. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19416520802211651

*Sargent, L. D., Allen, B. C., Frahm, J. A. & Morris, G. (2009). Enhancing the experience of student teams in large classes: Training teaching assistants to be coaches. Journal of Management Education, 33(5), 526-552. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1052562909334092

Sashittal, H. C., Jassawalla, A. R. & Markulis, P. (2011). Teaching students to work in classroom teams: A preliminary investigation of instructors' motivations, attitudes, and actions. Academy of Educational Leadership Journal, 15(4), 93-106. https://www.questia.com/read/1G1-263157469/teaching-students-to-work-in-classroom-teams-a-preliminary

*Seethamraju, R. & Borman, M. (2009). Influence of group formation choices on academic performance. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 34(1), 31-40. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602930801895679

Sykes, C., Moerman, L., Gibbons, B. & Dean, B. A. (2014). Re-viewing student teamwork: preparation for the 'real world' or bundles of situated social practices? Studies in Continuing Education, 36(3), 1-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0158037x.2014.904784

*Teo, S. T. T., Segal, N., Morgan, A. C., Kandlbinder, P., Wang, K. Y. & Hingorani, A. (2012). Generic skills development and satisfaction with groupwork among business students: Effect of country of permanent residency. Education + Training, 54(6), 472-487. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00400911211254262

Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency [TEQSA] (2016). Guidance note - Course design (including learning outcomes and assessment). Canberra: Australian Government. http://www.teqsa.gov.au/hesf-2015-specific-guidance-notes

Trigwell, K. & Prosser, M. (2014). Qualitative variation in constructive alignment in curriculum design. Higher Education, 67(1), 141-154. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10734-013-9701-1

*Troth, A. C., Jordan, P. J. & Lawrence, S. A. (2012). Emotional intelligence, communication competence, and student perceptions of team social cohesion. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 30(4), 414-424. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0734282912449447

Truscott, D. M., Swars, S., Smith, S., Thornton-Reid, F., Zhao, Y., Dooley, C., Williams, B., Hart, L. & Matthews, M. (2010). A cross-disciplinary examination of the prevalence of mixed methods in educational research:1995-2005. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 13(4), 317-328. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13645570903097950

Volkov, A. & Volkov, M. (2015). Teamwork benefits in tertiary education: Student perceptions that lead to best practice assessment design. Education + Training, 57(3), 262-278. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/ET-02-2013-0025

Volet, S. & Ang, G. (1998). Culturally mixed groups on international campuses: An opportunity for inter-cultural learning. Higher Education Research & Development, 17(1), 5-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0729436980170101

| Authors: Linda Riebe in the School of Business and Law at Edith Cowan University, teaches in the area of employability skills and is the Director of Academic Studies. Her primary research focus is currently in the area of teamwork, with particular focus on pedagogical practices in the higher education context. Email: l.riebe@ecu.edu.au Web: http://www.ecu.edu.au/schools/business-and-law/staff/profiles/lecturer/ms-linda-riebe Associate Professor Antonia Girardi in the School of Business and Governance at Murdoch University teaches in the areas of research methods and human resources management. In 2015, she was a recipient of the Murdoch University Vice Chancellor's Award for Excellence in Learning and Teaching for her work on building student self efficacy beliefs through the creation of a holding environment. Email: a.girardi@murdoch.edu.au Web: http://profiles.murdoch.edu.au/myprofile/antonia-girardi/ Dr Craig Whitsed in the Centre for University Teaching and Learning at Murdoch University teaches across a range of learning contexts and modes including academic professional development and training; postgraduate and undergraduate teaching; and hdr supervision. his primary research focus is in the area of internationalisation of the curriculum in higher education. Email: c.whitsed@murdoch.edu.au Web: http://profiles.murdoch.edu.au/myprofile/craig-whitsed/ Please cite as: Riebe, L., Girardi, A. & Whitsed, C. (2017). Teaching teamwork in Australian university business disciplines: Evidence from a systematic literature review. Issues in Educational Research, 27(1), 134-150. http://www.iier.org.au/iier27/riebe.html |