|

Communicative English language teaching in Egypt: Classroom practice and challenges

Mona Kamal Ibrahim

Al-Ain University of Science and Technology, United Arab Emirates, and Helwan University, Egypt

Yehia A. Ibrahim

Assiut University, Egypt

Following a "mixed methods" approach, this research is designed to examine whether teaching English as a foreign language (EFL) in Egypt's public schools matches the communicative English language teaching (CELT) approach. Qualitative and quantitative data were collected from 50 classroom observations, 100 questionnaire responses from teachers, and 10 face-to-face interviews with follow-up discussion sessions. The results indicated that, despite of all the CELT-demanding policies of the Egyptian Ministry of Education, practising teachers are mostly unaware of CELT principles and know-how implementation. Some key problems and challenges facing CELT implementation along with proposed solutions and recommendations are discussed.

There have been many definitions of communicative language teaching, however that of Richards, Platt and Platt (1992) in the Dictionary of language teaching and applied linguistics is a simple and straightforward one. Communicative language teaching in this dictionary is defined as "an approach to foreign or second language teaching which emphasizes that the goal of language learning is communicative competence". The teachers' role in the communicative competence context as pronounced by Czura (2016) is to develop knowledge, skills and attitudes in their students that will help them interact with interlocutors coming from different cultural, linguistic and national backgrounds. According to Crawford (2003), "Communicative approaches to second-language acquisition are based on concepts, theories, and hypotheses that converge around the constructivist paradigm". The constructivist theory of learning is based on the notion that learners construct their own ideas instead of receiving them complete and correct from the teacher or any source of authority. This process of construction is internal, individualised and unique. Constructivist teaching is based on problem-solving and inquiry-based learning activities, with which students formulate and test their ideas, draw conclusions and inferences, and pool and convey their knowledge in a collaborative learning environment. Constructivism transforms the student from a passive recipient of information to an active participant in the learning process.

It is the authors' belief that English language learners need a constructivist/com-municative approach to learning English as a second language because the opportunities for learning are authentic and are focused on meaning-making and problem-solving.

Communicative language teaching has been reasonably assumed (Widdowson, 1978; Savignon, 1983, 1990) to be based implicitly or explicitly on some model of communicative competence (e.g., Hymes, 1967, 1972). Following the economic, political, and technological changes of the 21st century, communicative language teaching seems to be the best known approach to teaching English as a second or foreign language. Egypt, like many other countries in the world, has been striving to improve English language teaching (Ginsburg & Megahed 2008 & 2011; Ginsburg 2010; Holliday, 1992, 1994, 1996; Snow et al., 2004; Warschauer, 2002).

In Egypt, English is seen as an extremely important subject. A good knowledge of English is regarded as a means of guaranteeing better job opportunities. However, in Egyptian public schools, teaching of the English language has been, for long time, based on the traditional approaches that focus on grammar, vocabulary, and translation without paying much attention to communication. Since the late seventies many Egyptian graduate students have obtained masters and/or PhD degrees in the field of teaching English as a second language (ESL) or as a foreign language (EFL) from western countries, wherein the learner's communicative competence has been upgraded to become the ultimate goal of teaching ESL/EFL. Upon return these scholars, have become active advocates emphasising the need for articulation and development of alternative approaches and methods of English teaching. Simultaneously, since the 1970s and the start of the reform movement, the Egyptian Ministry of Education (MOE) - supported by international aid agencies such as the World Bank, the British ODA (Overseas Development Administration), the European Union (EU), and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) - have directed tremendous efforts to teacher education (Kozma, 2005; El-Fiki 2012). These agencies have collaborated with several national and international higher education and research institutes, training centres, and specialists from the field of teaching English to speakers of other languages (TESOL) to raise teachers' efficacy, provide teachers with the necessary support through varied professional development opportunities, and improve language education, as well as introduce new national textbooks (Darwish, 2016).

Communicative language teaching (CLT) was the best alternative and the Egyptian government, with the help of these international organisations, has been campaigning for reforms in English teaching. In the early nineties, the Egyptian MOE defined some aims for teaching English as a first foreign language (Ministry of Education, 1994: 19-20). Since then the educational authorities in Egypt have been encouraging and preparing English student-teachers to adopt the CLT approach (Ibrahim, 2004). The Ministry's aims are summarised as follows: (1) to help students develop the ability to use English effectively for the purpose of communication in a variety of situations; (2) to assist students to develop an awareness of the nature of language and language-learning skills; and (3) to help students acquire a sound basis for the skills required for further study or employment using English. The Teachers' Guide produced by the MOE (Ministry of Education, 2000:12), which only exists in a hardcopy format, explained the presumed role of teachers within the communicative approach:

In order to help your students become 'learners', you have a varied role: to plan and manage the class; to be knowledgeable about what you are teaching and to provide a good model for pronunciation; to guide your students in the process of learning, helping them to think for themselves; to be ready to help with problems. In a communicative classroom, the aim is active involvement, interaction of teacher with students, and of students with students, where language is used, and where real learning can take place. ..... your role is to help your students to take responsibility for assessing their own weaknesses and to ask for more practice or remedial help when they need it.

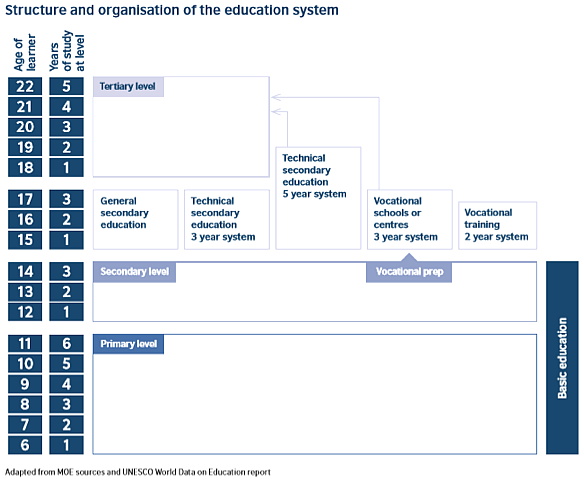

The pre-university secular education structure includes the following stages: pre-school education stage (kindergarten) which is an independent educational stage lasting two years for children aged 4-6; compulsory basic education stage which starts at the age of 6 and includes primary and preparatory education. Finally, there is the secondary education stage from age 15 to 17. This stage comprises four subgroups: general secondary, technical, commercial and agricultural. Learners join any of these subgroups according to their performance on the Basic Education Examination at the end of the preparatory stage.

Alongside this system, which is provided free to Egyptian citizens, there is a private education sector, divided in the same way and under the Ministry of Education supervision, but demanding high fees. Figure 1 illustrates the Egyptian education system.

In the context of Egyptian educational reform where the CLT approach has been explicitly promoted as a way to improve teaching, the quality of teaching English in classrooms can really be an influential factor affecting students' motivation as well as their attitudes towards learning English (Al-Sohbani,1997). The current study was designed and executed to provide a clear picture of the teaching method applied in teaching English in Egypt, and examine whether or not English teachers understand the basic principles of CLT. In the present research the term 'CELT' is adopted by the authors to specify English as the foreign language in the CLT approach, as an abbreviation for 'Communicative English Language Teaching'. In line with the above mentioned objectives, the research questions were formulated as follows:

Figure 1: Structure of the Egyptian pre-university education system

(McIlwraith & Fortune, 2016)

Out of the various mixed method designs presented by Morse (1991) and later by Creswell et al. (2003), the present research adopts the sequential explanatory design. According to Creswell et al. (2003), this design is "characterized by the collection and analysis of quantitative data followed by the collection and analysis of qualitative data", where extra emphasis is given to the quantitative data, and then both methods are integrated in the interpretation phase of the study. One of the advantages of this design, as Morse (1991) pointed out, is that the qualitative data are useful in examining in detail any unexpected results that may arise from the quantitative data.

The sequential explanatory design was a good fit in the current study because of its congruency with the quantitative aspect of the study. The aim of capturing the reality and experiences of the English language teachers was much enhanced by the qualitative data obtained from the interviews, which followed the quantitative data collection from observations and questionnaires.

To guarantee the validity of the work presented in the present research study, the authors have attempted to accomplish what Sarantakos (1993) referred to as 'argumentative validation' and 'ecological validation'. Argumentative validation is established through presentation of findings in such a way that conclusions can be followed and tested. Ecological validation is established through carrying out the research in the natural environment of the students and the teachers, which is the schools, the staff room, and the classrooms.

By choosing research instruments that are suitable and significant for the study purpose, the authors are also achieving 'internal validity'. One of the suggested ways of achieving a higher degree of validity is the use of triangulation of data and methods. "Triangulation techniques in social sciences attempt to map out, or explain more fully, the richness and complexity of human behaviour by studying it from more than one stand point" (Cohen, Manion & Morrison, 2001). Of the principal types of triangulation used in research, the present study used data, methodological, and space triangulation.

The observation checklist consisted of 40 statements on a Likert scale. These items were designed to capture the extent to which CLT was implemented as an official approach adopted by the Egyptian MOE. Teachers responded to the 40 items on a 5-point rating scale (4 = always, 3 = frequently, 2 = sometimes, 1 = rarely, 0 = never) (Appendix A). The scaled checklist was used by the researchers in order to increase the reliability of collected data as well as to reduce the impact of the expectations of the first author as observer. The researchers arranged the 40 items in the CELT observation checklist into five main categories (Table 1 and Appendix A).

| No. | CELT categories | Statement number in the observation checklist |

| 1 | Lesson planning | 14, 15, 18, 19, 20, 21 |

| 2 | Lesson content | 8, 17, 22, 25, 26 |

| 3 | Classroom environment | 30, 31, 32, 33, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39 |

| 4 | Teaching performance | 5, 6, 11, 12, 23, 24, 27, 28, 29, 34 |

| 5 | CELT framework principles | 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 9, 10, 13, 16, 40 |

The checklist was designed and implemented in English. A panel of English language and English methodology professors, four from Helwan University and three from Akhbar El-Yom Academy, undertook validation of the checklist and accepted it as reflecting CLT principles.

The checklist items (Table 1) were based on the following ten features of CLT, which also have much in common with constructivist principles in teaching and learning:

The first author of this manuscript carried out the English teaching classroom observations in five secondary public schools in Giza governorate, Egypt. Two English teachers were randomly selected in each school for the observation protocol and their classrooms were observed every second week for a total of five observation visits. A total of 50 observations were conducted, using 40 checklist items, thereby obtaining an overall number of 2000 observed remarks.

Three questions were formed to address whether or not teachers practice the CELT approach in their classes. Teachers were required to choose one of the following frequency words to describe their performance: "always, frequently, sometimes, rarely, never". The questions were:

Q1 - Do you think the students are motivated to learn EFL?

Q2 - How can a CELT environment be created in the classroom?

Q3 - Do you face any difficulties in implementing the CELT? Administrative, facilities, ... etc.

The interviews addressed the first research question of the study, as well as identifying the problems the teachers perceived in implementing CELT and preventing them from following this approach (i.e. "by the book"). The first question served as an "ice breaker" besides probing teachers' perceptions of students' motivation to learn EFL, which plays a major role in the successful implementation of a communicative, constructivist classroom environment.

| Instrument | No. of teachers | Frequency of admin- istration | Total no. admin- istered | No. of schools | Language of admin- istration | Type of data gathered |

| Questionnaire | 100 | 1 | 100 | 9 | English | quanti- tative |

| Observation checklist | 10 (from the 100) | 5 | 50 | 5 | English | quanti- tative |

| Interview | 10 (from the 100) | 1 | 10 | 5 | Arabic | quali- tative |

Wherein the numerator value (the categorical score) is the summation of the score for each statement in each category multiplied by its frequency observation score (always = 4; frequently = 3; sometimes = 2; rarely = 1; never = 0). The denominator in the equation is a product of the number of items that belong to each category multiplied by the number of their observations (50) and the maximum score for each item (4). Further explanation of this equation is given in the Results and Discussion sections.

| No. | CELT categories | Statement number in the observation checklist | Total score | % of total score |

| 1 | Lesson planning | 14, 15, 18, 19, 20, 21 | 131 | 10.9 |

| 2 | Lesson content | 8, 17, 22, 25, 26 | 242 | 30.3 |

| 3 | Classroom environment | 30, 31, 32, 33, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39 | 429 | 23.8 |

| 4 | Teaching performance | 5, 6, 11, 12, 23, 24, 27, 28, 29, 34 | 339 | 17.0 |

| 5 | CELT principles* | 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 9, 10, 13, 16, 40 | 41 | 2.1 |

| Average % of CELT implementation | 16.8 | |||

| * CELT principles: Target language use; fluency vs. accuracy; correction purpose; grammar in communication; language skills. | ||||

In order to explain how the equation was applied to generate the category data in Table 3 from the observations of individual statements (or items) shown in Table 1, consider a calculation example of the first category, i.e. lesson planning. Lesson planning was observed using six statements in the observation checklist (statements 14, 15, 18, 19, 20 and 21). The calculation example is depicted in Table 4, noting that the checklist included 50 observations for each statement (5 schools x 2 teachers x 5 visits) that were distributed according to the degree of their CELT practice according to the scale: always = 4; frequently = 3; sometimes = 2; rarely = 1; and never = 0, see Table 5.

By considering "lesson content" and "lesson planning" as one category that occurs prior to classroom implementation, one can find out that the checklist indicators are well-distributed among the CELT categories. Some of the CELT indicator statements occur in more than one category but they have differences in their relative closeness to each category. This is expected, based on CELT implementation being an ecological and holistic approach with interrelated and interdependent factors. The highest percentage of total scores (30.3%) was related to "lesson content" (category 2). This is predicted and supports the literature discussed previously, indicating that the content is pre-set by the MOE in line with CLT curriculum design principles. In order to provide a valid decision regarding the 'lesson planning' category, the researcher conducting the observation asked to see the teachers' planning.

A key feature of the communicative approach to language teaching is to use the target language, in this case English, as often as possible. In fact, Table 3 also reveals that, despite the teachers' awareness of the MOE adoption policy of CELT in teaching English as a foreign language, the worst percentage (2.1%) was for teachers' implementation of CELT framework principles (category 5). Arabic was the dominant language used in all the classes observed, as it probably is in most English classes in Egypt. English was not used for any real communication; the English used by teachers as well as students was restricted to reading the textbook and answering the drills. Data indicate that the teachers nearly all lack awareness and a clear conception of the communicative competence approach. The last row of Table 3 records that only 16.8% of the overall English teaching is attaining the CELT approach, or, more than 80% of the teaching dynamics is not in accord with CELT.

| Statement no. | Score of individual item =  | |

| 14 15 18 19 20 21 |

[(0 x 4) + (0 x 3) + (5 x 2) + (7 x 1) + (38 x 0)] = 17 [(1 x 4) + (2 x 3) + (2 x 2) + (2 x 1) + (43 x 0)] = 16 [(5 x 4) + (5 x 3) + (5 x 2) + (5 x 1) + (30 x 0)] = 50 [(1 x 4) + (1 x 3) + (3 x 2) + (7 x 1) + (38 x 0)] = 20 [(0 x 4) + (0 x 3) + (0 x 2) + (0 x 1) + (50 x 0)] = 0 [(1 x 4) + (2 x 3) + (6 x 2) + (6 x 1) + (35 x 0)] = 28 | |

Total score of the lesson planning category |

17 + 16 + 50 + 20 + 0 + 28 = 131 | |

| Percentage of performing the lesson planning category as related to its CELT-best practice |  | |

| CELT category | Statement | Frequency incidences wherein the teachers' practice meets the observed statement | Total | ||||

| Always | Frequ- ently | Some- times | Rarely | Never | |||

| Lesson planning | 14. Teacher plans lesson to emphasise English language in use. | 0 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 38 | 50 |

| 15. Teacher balances language, culture and the subject content goals in lesson plans. | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 43 | 50 | |

| 18. Teacher designs class-room activities to include experiences with literature or authentic sources from social life and target culture(s). | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 30 | 50 | |

| 19. Teacher plans activities that provide students with successful learning experiences. | 1 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 38 | 50 | |

| 20. Teacher plans the lesson to incorporate both new and familiar material. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 | |

| 21. Teacher carefully plans, and follows up, individual activities as important part of the overall activities. | 1 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 35 | 50 | |

The overall practice of the 10 teachers compared to the ideal CELT approach was calculated as percentage of the number of checks of each frequency term (Table 6 and Figure 2). Figure 2 shows the marked increase from relatively small 'Always' to 'Rarely' frequencies, to the relatively large 'Never' indicating that the practices of the observed teachers were far below the CELT standards.

| Frequency incidences wherein the teachers' practice meets the observed statement | Total | |||||

| Always | Frequently | Sometimes | Rarely | Never | ||

| Total | 103 | 104 | 142 | 174 | 1477 | 2000 |

| % | 5.15 | 5.20 | 7.10 | 8.70 | 73.85 | 100 |

Figure 2: Frequency of classroom observations of CELT being

practised in five public Egyptian schools. N=2000.

Classroom observations have also shown the following dominant practices:

Figure : Answers by 100 teachers to a 3-item questionnaire about the extent of their CELT practice

| T1: | Yes absolutely. There are even some students who could excel their colleagues in the private schools. A lot of them like the English language. |

| T2: | Yes, they like it very much. However, there are occasions where the students hate the language because of the teacher. It all depends on the teacher. |

| T3: | Yes, some students have very high motivation. |

Other teachers had different opinions and perceived a connection between student motivation for learning the language and academic achievement in the language, for example:

| T5: | Not all of them, and there is a wide range in their level. For instance, in last month's written test their grades ranged from 5 till 19 out of 25. |

| T4: | Even if the syllabus does not do that, it is the teacher's duty to try and establish this in class. |

While another expressed the difficulty of establishing such situation:

| T2: | It is very hard for us, as teachers, to perform this without any guidance from the inspector or the head teacher. |

Other teachers stated the reason behind such difficulty:

| T5: | Many other teachers do not bother; they care most about the final grades. |

| T1: | We were not really given clear instructions on how to implement this. |

| T3: | We are not used to it and neither are the students, every teacher tries out and experiments in his own way. |

1. Class size

The large sizes of classes, naturally, have negative effects on the quality of teaching and learning processes inside classes. Teachers in such crowded classes face numerous difficulties with respect to wide ranges of linguistic ability and motivation. In such conditions, discipline is a major problem, especially in a system where discipline is considered as very important. Teachers do not like the noise from other classes. If students talk at the same time or become over-enthusiastic, the class becomes "unacceptably" noisy. Thus, student involvement is very restricted. This is just the opposite of the type of environment which is considered to be positive for communicative language teaching.

2. Lack of resources

Egyptian schools depend solely on the MOE for all supplies. Due to pressing economic conditions, this dependence provides only small budget for schools. Teaching aids do not go beyond the traditional: blackboard and chalk.

| T1: | I use tapes very rarely, this is because most classrooms do not have working power points. Sometimes there aren't enough tape recorders to use because most of them are out of order. |

| T4: | Very often we have a power failure, which is a very common phenomenon in Egypt. As a result, I depend mainly on my reading; especially that the students find it very difficult to understand foreign speakers. |

It is worth pointing out that the teachers are referring to tapes and tape recorders as facilities, even though these are now obsolete technologies.

3. The existence of a double-shift system

Because of the increase in population, and the lack of resources and funding, two sessions are held every day in the same school building. These two sessions represent two different schools. One session starts from 8.00 am to 12.00 noon and the other from 12.30 pm to 4.30 pm. This system reduces the teaching hours per day with the result that the duration of all periods, including English, is shortened. At least five minutes are lost from the lesson for administrative matters such as attendance records and teachers moving between classrooms. This has negative effects on learner-oriented teaching performance.

4. Examination-oriented teaching

Egyptian students at all levels tend to be examination oriented. Teachers spend most of the class time preparing students for exams, by giving them readily answered questions covering the novel, or written letter samples around the popular topics that come in the tests, for rote learning, instead of helping the students to practise using English, and develop their competence in language production and comprehension.

| T4: | Yes, of course. I provide them with leaflets covering different aspects of the curriculum: grammar, novel... how to write a paragraph; different ideas and sentences to include in different paragraphs, how to write a letter, so they would study these notes and get good marks in the exam. |

| T1: | There is a regular monthly written test. As for listening, we usually use those marks for attendance, behaviour, and participation. |

This finding also agrees with the World Bank which found that evidence of improvement is still limited (World Bank, 2007). El-Fiki (2012) and references therein suggested a number of factors impede CELT implementation, e.g., social psychological factors such as people's attitudes and their deeply rooted traditional beliefs about teaching and learning; economic factors including the lack of sufficient funds, resources, and materials; educational factors such as system imposed regulations, curriculum issues related to goals, content and assessment, teacher preparation, the entrenched views on what constitutes appropriate language teaching and learning, and environmental and physical settings (such as room conditions, class size, etc.).

As for the second research question, addressing the degree of implementation of CELT in classrooms, the outcomes seem to be disappointing, as students in secondary schools are still struggling to achieve the desired level of proficiency in English. This can be concluded from the observation checklist results which clearly indicate a serious divergence from CELT best practice. The teachers are not up to the approach, and the classroom environment and resources are too limited.

The results indicate that CELT is not the norm in public schools, and it is unfortunate that there are still many obstacles that prevent even experienced teachers from adopting CELT. In addition to the reasons brought forward by the teachers, the authors believe that traditional, grammar-based examinations, lack of spare time for preparing communicative materials to supplement the MOE's text-based materials, and anxiety among students are also factors in the problem. Another problematic aspect of the communicative approach is that it requires teachers who are competent in the English language. Teachers should 'possess a very high level of competence ... always prepared for any linguistic emergency' (Marton, 1988). This is a problem in the Egyptian context where very few teachers have had the opportunity to achieve high levels of proficiency in speaking the language, in their academic institutes or their personal life. The authors also believe that teachers have to believe strongly in the CELT approach in order to create an effective, student-centred learning environment.

It is unfortunate to find that despite the training and education funds that have been spent, there is low return on investment. The process of teacher preparation is instrumental but not magic in the transition of English teaching methods to communicative competence; other factors are just as important as teacher competency. CELT requires four groups of roles: the teachers, the students/learners, the instructional materials and educational system, along with school administration. The educational system and school administration in many developing countries may exaggerate the level of performance and outcomes. As the role of a CELT teacher is diverse (facilitator, resource organiser, guide, researcher, learner, analyst, counsellor, group-dynamic orchestrator, etc.), training becomes instrumental for CELT implementation and effectiveness. The authors believe that because English teachers in Egyptian public schools are non-native English speakers, lack of communicative language proficiency among them may add one more reason why training is seriously needed. The required change in students' role is a feature of the communicative approach that is problematic in cultures where learners are traditionally expected to be recipients of knowledge rather than active participants in its creation.

These concerns will require much attention if CELT is to continue to gain practical momentum in the future. The findings from the present study can provide Egyptian EFL teachers, educators, policy makers and interested scholars with information about the current state of CELT performance in Egypt, and, as summarised below, recommendations for progressing the adoption of CELT.

Abukhattala, I. (2016). The use of technology in language classrooms in Libya. International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, 6(4), 262-267. http://www.ijssh.org/vol6/655-H019.pdf

Al-Sohbani, Y. A. (1997). Attitudes and motivations of Yemeni secondary school students and English language learning. Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Pune, India.

Al-Sohbani, Y. A. (2013). An exploration of English language teaching pedagogy in secondary Yemeni education: A case study. International Journal of English Language and Translation Studies, 1(3), 41-57. http://www.eltsjournal.org/archive/value1%20issue3/4-1-3-13.pdf

Alsowat, H. H. (2016). Foreign language anxiety in higher education: A practical framework for reducing FLA. European Scientific Journal, 12(7), 193-220. http://dx.doi.org/10.19044/esj.2016.v12n7p193

Asassfeh, S. M., Khwaileh, F. M., Al-Shaboul, Y. M. & Alshboul, S. S. (2012). Communicative language teaching in an EFL context: Learners' attitudes and perceived implementation. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 3(3), 525-535. http://dx.doi.org/10.4304/jltr.3.3.525-535

Bataineh, R. F., Bataineh, R. F. & Thabet, S. S. (2011). Communicative language teaching in the Yemeni EFL classroom: Embraced or merely lip-serviced? Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 2(4), 859-866. http://dx.doi.org/10.4304/jltr.2.4.859-866

Brumfit, C. & Johnson, K. (Eds.) (1979). The communicative approach to language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Burns, A. & Richards, J. (Eds.) (2009). The Cambridge guide to second language teacher education. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Canale, M. (1983). From communicative competence to communicative language pedagogy. In J. C. Richards & R. W. Schmidt (Eds.), Language and communication. London: Longman.

Cohen, L., Manion, L. & Morrison, K. (2001). Research methods in education. London: Routledge Falmer.

Coskun, A. (2011). Investigation of the application of communicative language teaching in the English language classroom Ð a case study on teachers' attitudes in Turkey. Journal of Linguistics and Language Teaching, 2(1), 85-109. https://sites.google.com/site/linguisticsandlanguageteaching/home-1/volume-2-2011-issue-1/volume-2-2011-issue-1---article-coskun

Crawford, A. N. (2003). Communicative approaches to second-language acquisition: A bridge to reading comprehension. In G. G. Garcia (Ed.), English learners: Reaching the highest level of English literacy (pp. 152-178). Newark, DE: International Reading Association, Inc.

Creswell, J. W., Plano-Clark, V. L., Gutman, M. L. & Hanson, W. E. (2003). Advanced mixed methods research designs. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research (pp. 209-240). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Ivankova, N. V., Creswell, J. W. & Stick, S. L. (2006). Using mixed methods sequential explanatory design: From theory to practice. Field Methods, 18(1), 3-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177%2F1525822X05282260

Czura, A. (2016). Major field of study and student teachers' views on intercultural communicative competence. Language and Intercultural Communication, 16(1), 83-98. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2015.1113753

Darwish, H. (2016). Teachers' attitudes and techniques towards EFL writing in Egyptian secondary schools. International Journal for 21st Century Education, 3(1), 37-57. https://www.uco.es/servicios/ucopress/ojs/index.php/ij21ce/article/view/5646/5316

El-Fiki, H. A. (2012). Teaching English as a foreign language and using English as a medium of instruction in Egypt: Teachers' perceptions of teaching approaches and sources of change. Doctoral thesis, University of Toronto. https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/32705

Fairley, M. J. & Fathelbab, H. (2011). Reading and writing communicatively: Six challenges addressed. AUC TESOL Journal, Issue 1. https://www3.aucegypt.edu/auctesol/Default.aspx?issueid=8b20d438-2b85-4462-9f25-9be82e3c63dc&aid=f44173fb-bb5e-45b3-9521-2c5d72fab152

Farooq, M. U. (2015). Creating a communicative language teaching environment for improving students' communicative competence at EFL/EAP. International Education Studies, 8(4). http://www.ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/ies/article/view/47009

Ginsburg, M. (2010). Improving educational quality through active-learning pedagogies: A comparison of five case studies. Educational Research, 1(3), 62-74. http://www.interesjournals.org/full-articles/improving-educational-quality-through-active-learning-pedagogies-a-comparison-of-five-case-studies.pdf?view=inline

Ginsburg, M. & Megahed, N. (2008). Global discourses and educational reform in Egypt: The case of active-learning pedagogies. Mediterranean Journal of Educational Studies, 13(2), 91-115. https://www.um.edu.mt/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/60747/91-115_Ginsburg-Megahed.pdf

Ginsburg, M. & Megahed, N. (2011). Globalization and reform of faculties of education in Egypt: The roles of individual and organizational, national and international actors. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 19(15), 1-24. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ931648

Greene, J. (2007). Mixed options in social inquiry. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Han, I. (2016). (Re)conceptualisation of ELT professionals: Academic high school English teachers' professional identity in Korea. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 22(5), 586-609. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2016.1158467

Hismanoglu, M. & Hismanoglu, S. (2013). A qualitative report on the perceived awareness of pronunciation instruction: Increasing needs and expectations of prospective EFL teachers. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 22(4), 507-520. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40299-012-0049-6

Holliday, A. (1992). Tissue rejection and informal orders in ELT projects: Collecting the right information. Applied Linguistics, 13(4), 403-424. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/13.4.403

Holliday, A. (1994). Appropriate methodology in social context. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Holliday, A. (1996). Large- and small-class cultures in Egyptian university classrooms: A cultural justification for curriculum change. In H. Coleman (Ed.), Society and the language classroom (pp. 86-104). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Howatt, A. (1984). A history of English language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Huang, S. J. & Liu, H. F (2000). Communicative language teaching in a multimedia language lab. The Internet TESL Journal, 6(2), 1-7. http://iteslj.org/Techniques/Huang-CompLab.htm

Hymes, D. H. (1966). Two types of linguistic relativity (with examples from Amerindian ethnography). In W. Bright (Ed.), Sociolinguistics: Proceedings of the UCLA Sociolinguistics Conference. The Hague: Mouton, pp. 114-167.

Hymes, D. H. (1967). Models of the interaction of language and social setting. Journal of Social Issues, 23(2), 8-28. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1967.tb00572.x

Hymes, D. (1972). On communicative competence. In J. B. Pride & J. Holmes (Eds.), Sociolinguistics: Selected readings. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.

Ibrahim, M. K. (2004). The challenges of teaching English as a foreign language to Egyptian students with visual impairment. Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Manchester, UK.

Kozma, R. B. (2005). National policies that connect ICT-based education reform to economic and social development. Human Technology, 1(2), 117-159. http://humantechnology.jyu.fi/archive/vol-1/issue-2/kozma1_117-156/@@display-file/fullPaper/kozma.pdf

Leung, C. & Scarino, A. (2016). Reconceptualizing the nature of goals and outcomes in language/s education. The Modern Language Journal, 100(S1), 81-95. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/modl.12300

Littlewood, W. (1981). Communicative language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Marton, W. (1988). Methods in English language teaching: Frameworks and options. New York: Prentice Hall.

McIlwraith, H. & Fortune, A. (2016). English language teaching and learning in Egypt: An insight. London: British Council. https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/sites/teacheng/files/F239_English%20Language%20in%20Egypt_FINAL%20web.pdf

Ministry of Education (1994). The curriculum of secondary stage. Cairo: Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education (2000). The new English syllabus: Aims and implementation. Cairo: Ministry of Education.

Morse, J. M. (1991). Approaches to qualitative-quantitative methodological triangulation. Nursing Research, 40(2), 120-123.

Nattinger, J. R. (1984). Communicative language teaching: A new metaphor. TESOL Quarterly, 18(3), 391-407. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3586711

Nunan, D. (1987). Communicative language teaching: Making it work. ELT Journal, 41(2), 136-145. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/41.2.136

Nunan, D. (1989). Designing tasks for the communicative classroom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Razmjoo, S. A. & Riazi, A.-M. (2006). Do high schools or private institutes practice communicative language teaching? A case study of Shiraz teachers in high schools and institutes. The Reading Matrix, 6(3). http://www.readingmatrix.com/articles/razmjoo_riazi/article.pdf

Richards, J., Platt, J. & Platt, H. (1992). Dictionary of language teaching and applied linguistics. London: Longman.

Rowe, A. (2016). An overview of communicative language teaching (CLT). http://epi.sc.edu/~alexandra_rowe/FOV3-001000C1/S0017DD4D

Safari, P. & Rashidi, N. (2015). Teacher education beyond transmission: Challenges and opportunities for Iranian teachers of English. Issues in Educational Research, 25(2), 187-203. http://www.iier.org.au/iier25/safari.html

Sarantakos, S. (1993). Social research. London: Macmillan.

Savignon, S. J. (1983). Communicative competence: Theory and classroom practice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Savignon, S. J. (1990). Communicative language teaching: Definitions and directions. In J. E. Alatis (Ed.), Georgetown University Round Table on Language and Linguistics, pp. 202-217. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Savignon, S. J. (2002). Interpreting communicative language teaching: Contexts and concerns in teacher education. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Savignon, S. J. & Wang, C. (2003). Communicative language teaching in EFL contexts: Learner attitudes and perceptions. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 41(3), 223-249. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral.2003.010

Snow, M. A., Omar, M. & Katz, A. (2004). The development of EFL standards in Egypt: Collaboration among native and non-native English-speaking professionals. In L. D. Kamhi-Stein (Ed.), Learning and teaching from experience: Perspectives on non-native English speaking professionals (pp. 307-323). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Teddlie, C. & Tashakkori, A. (2003). Major issues and controversies in the use of mixed methods in the social and behavioral sciences. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research (pp. 3-50). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Warschauer, M. (2002). A developmental perspective on technology in language education. TESOL Quarterly, 36(3), 453-475. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3588421

White, C. J. (1989). Negotiating communicative language teaching in a traditional setting. ELT Journal, 43(3), 213-220. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/43.3.213

Widdowson, H. G. (1972). The teaching of English as communication. In C. Brumfit & K. Johnson (Eds.), The communicative approach to language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Widdowson, H. G. (1973). Directions in the teaching of discourse. In C.Brumfit & K. Johnson (Eds.), The communicative approach to language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Widdowson, H. G. (1978). Teaching language as communication. London: Oxford University Press.

Widdowson, H. G. (1990). Aspects of language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Widdowson, H. G. (1996). Comment: Authenticity and autonomy in ELT. ELT Journal, 50(1), 67-68. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/50.1.67

World Bank (2007). Egypt - Education enhancement program. Washington, DC: World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/873721468258319414/Egypt-Education-Enhancement-Program-Project

Wyatt, M. (2009). Practical knowledge growth in communicative language teaching. ESL-EJ, 13(2). http://www.tesl-ej.org/wordpress/issues/volume13/ej50/ej50a2/

| No. | Statement | Number of observations that follows the statement at the underneath score | ||||

| Always | Frequently | Sometimes | Rarely | Never | ||

| 1 | Teacher uses target English as the normal and expected means of classroom communication. | |||||

| 2 | Teacher keeps use of the native (Arabic) language totally separated from use of English unless it is absolutely necessary. | |||||

| 3 | Teacher avoids dominating the talk-time and does not rely on a word-for-word Arabic translation to explain meanings. | |||||

| 4 | Teacher focuses on student's meaningful fluency rather than form/ structure/ grammar accuracy while communicating in English. | |||||

| 5 | Teacher provides students with opportunities for extended listening. | |||||

| 6 | Teacher uses authentic and social life communication to motivate English language use. | |||||

| 7 | Teacher corrects students' errors with primary focus on exchangeable meaning rather than structure or form. | |||||

| 8 | Teacher provides students with hands-on realistic situations and experiences accompanied by oral and written use of English. | |||||

| 9 | Teacher accelerates communication by teaching class functional chunks of the English language. | |||||

| 10 | Teacher makes sure that reading and writing for communication are strongly complemented and integrated with listening and speaking. | |||||

| 11 | Teacher uses questions and activities that provide real exchange of students' knowledge and opinions. | |||||

| 12 | Teacher encourages students to ask questions as well as to answer others' questions. | |||||

| 13 | Teacher introduces and practices grammatical structures and vocabularies in meaningful communication contexts. | |||||

| 14 | Teacher plans lesson to emphasise English language in use. | |||||

| 15 | Teacher balances language, culture and the subject content goals in lessons plans. | |||||

| 16 | Teacher presents grammar through, and for, usage rather than critical analysis. | |||||

| 17 | Teacher draws information and experiences from the social life and target culture(s). | |||||

| 18 | Teacher designs classroom activities to include experiences with literature or authentic sources from social life and target culture(s). | |||||

| 19 | Teacher plans activities that provide students with successful learning experiences. | |||||

| 20 | Teacher plans the lesson to incorporate both new and familiar material. | |||||

| 21 | Teacher carefully plans, and follows up, individual activities as important part of the overall activities. | |||||

| 22 | Teacher makes sure that the lesson, content and activities are appropriate to age and developmental level of the class and to the target culture(s). | |||||

| 23 | Teacher provides logical, smooth and timely transition from one activity to the other. | |||||

| 24 | Teacher gives clear classroom directions and concise examples and keeps English learning as a student-centred process. | |||||

| 25 | Teacher gives many, varied and concrete materials and uses a diversity of classroom techniques and strategies to cope with different learning styles. | |||||

| 26 | Teacher uses visual and audio techniques as well as role play dramatisation and group activities effectively to cover all learning styles. | |||||

| 27 | Teacher allows ample wait time after questions. | |||||

| 28 | Teacher maintains a pace that keeps the learning momentum and creates a sense of direction. | |||||

| 29 | Teacher gives activities and games frequently to fit the lesson content and English communication outcomes rather timely and logically. | |||||

| 30 | Teacher makes sure that no student is left behind and all students are active throughout the class period both indiv-idually and in pairs or groups. | |||||

| 31 | Teacher encourages and balances all patterns of interaction (teacher/ student, student/ teacher, student/ student). | |||||

| 32 | Teacher prevents unbalanced or dominating participation in group activities. | |||||

| 33 | Teacher appears enthusiastic and motivated while in a two-way communication of English to his/her class. | |||||

| 34 | Teacher shows patience with student attempts to commun-icate fully in English and acknowledge students' differ-ences in their level of fluency. | |||||

| 35 | Teacher gives students timely, varied, appropriate and motivating feedback. | |||||

| 36 | Teacher leads the class positively, promptly and in a non-disruptive or intrusive way. | |||||

| 37 | Teacher is fully aware of students' level of enthusiasm and motivation. | |||||

| 38 | Teacher makes him/her self and students feel the gladness and happiness of being a member of the English class. | |||||

| 39 | Teacher attracts other students to join his class and learn English for life not just for the final exam. | |||||

| 40 | Teacher balances the score of classroom testing in terms of communication, i.e., to emphasise reading, writing, listening, and speaking. | |||||

| CELT category | Statement | Frequency incidences wherein the teachers' practice meets the observed statement | Total | ||||

| Always | Frequ- ently | Some- times | Rarely | Never | |||

| Lesson planning | 14. Teacher plans lesson to emphasise English language in use. | 0 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 38 | 50 |

| 15. Teacher balances language, culture and the subject content goals in lessons plans. | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 43 | 50 | |

| 18. Teacher designs classroom activities to include experiences with literature or authentic sources from social life and target culture(s). | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 30 | 50 | |

| 19. Teacher plans activities that provide students with successful learning experiences. | 1 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 38 | 50 | |

| 20. Teacher plans the lesson to incorporate both new and familiar material. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 | |

| 21. Teacher carefully plans, and follows up, individual activities as important part of the overall activities. | 1 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 35 | 50 | |

| Lesson content | 8. Teacher provides students with hands-on realistic situations and experiences accompanied by oral and written use of English. | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 37 | 50 |

| 17. Teacher draws information and experiences from the social life and target culture(s). | 5 | 7 | 9 | 8 | 21 | 50 | |

| 22. Teacher makes sure that the lesson, content and activities are appropriate to age and developmental level of the class and to the target culture(s). | 15 | 15 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 50 | |

| 25. Teacher gives many, varied and concrete materials and uses a diversity of classroom techniques and strategies to cope with different learning styles. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 | |

| 26. Teacher uses visual and audio techniques as well as role play dramatisation and group activities effectively to cover all learning styles. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 35 | 50 | |

| Class- room environ- ment | 30. Teacher makes sure that no student is left behind and all students are active throughout the class period both individually and in pairs or groups. | 5 | 6 | 15 | 4 | 20 | 50 |

| 31. Teacher encourages and balances all patterns of interaction (teacher/student, student/teacher, student/student). | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 46 | 50 | |

| 32. Teacher prevents unbalanced or dominating participation in group activities. | 5 | 4 | 2 | 9 | 30 | 50 | |

| 33. Teacher appears enthusiastic and motivated while in a two-way communication of English to his/her class. | 8 | 10 | 12 | 7 | 13 | 50 | |

| 35. Teacher gives students timely, varied, appropriate and motivating feedback. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 46 | 50 | |

| 36. Teacher leads the class positively, promptly and in a non-disruptive or intrusive way. | 5 | 7 | 11 | 12 | 15 | 50 | |

| 37. Teacher is fully aware of students' level of enthusiasm and motivation. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 46 | 50 | |

| 38. Teacher makes him/her self and students feel the gladness and happiness of being a member of the English class. | 2 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 37 | 50 | |

| 39. Teacher attracts other students to join his class and learn English for life not just for the final exam. | 10 | 5 | 12 | 8 | 15 | 50 | |

| Teaching perfor- mance | 5. Teacher provides students with opportunities for extended listening. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 40 | 50 |

| 6. Teacher uses authentic and social life communication to motivate English language use. | 5 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 25 | 50 | |

| 11. Teacher uses questions and activities that provide real exchange of students' knowledge and opinions. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 38 | 50 | |

| 12. Teacher encourages students to ask questions as well as to answer others' questions. | 8 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 23 | 50 | |

| 23. Teacher provides logical, smooth and timely transition from one activity to the other. | 1 | 3 | 2 | 11 | 33 | 50 | |

| 24. Teacher gives clear classroom directions and concise examples and keeps English learning as a student-centered process. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 46 | 50 | |

| 27. Teacher allows ample wait time after questions. | 10 | 3 | 7 | 12 | 18 | 50 | |

| 28. Teacher maintains a pace that keeps the learning momentum and creates a sense of direction. | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 44 | 50 | |

| 29. Teacher gives activities and games frequently to fit the lesson content and English communication outcomes rather timely and logically. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 | |

| 34. Teacher shows patience with student attempts to communicate fully in English and acknowledge students' differences in their level of fluency. | 3 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 31 | 50 | |

| CELT frame- work principles | 1. Teacher uses target English as the normal and expected means of classroom communication. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 48 | 50 |

| 2. Teacher keeps use of the native (Arabic) language totally separated from use of English unless it is absolutely necessary. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 | |

| 3. Teacher avoids dominating the talk-time and does not rely on a word-for-word Arabic translation to explain meanings. | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 47 | 50 | |

| 4. Teacher focuses on student's meaningful fluency rather than form/structure/grammar accuracy while communicating in English | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 49 | 50 | |

| 7. Teacher corrects students' errors with primary focus on exchangeable meaning rather than structure or form. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 | |

| 9. Teacher accelerates communication by teaching class functional chunks of the English language. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 | |

| 10. Teacher makes sure that reading and writing for communication are strongly complemented and integrated with listening and speaking. | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 42 | 50 | |

| 13. Teacher introduces and practices grammatical structures and vocabularies in meaningful communication contexts. | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 47 | 50 | |

| 16. Teacher presents grammar through, and for, usage rather than critical analysis. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 46 | 50 | |

| 40. Teacher attracts other students to join his class and learn English for life not just for the final exam. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 | |

| Total | 103 | 104 | 142 | 174 | 1477 | 2000 | |

| % | 5.15 | 5.20 | 7.10 | 8.70 | 73.85 | 100 | |

| Authors: Dr Mona Kamal Ibrahim (corresponding author) is Deputy Dean and Head of English Department, College of Education, Humanities and Social Studies, Al-Ain University of Science and Technology, United Arab Emirates. She is on a sabbatical leave from the Faculty of Education, Helwan University, Egypt. She received her PhD in the philosophy of education from Manchester University, UK. She has a long experience in teaching English language skills as well as methods of teaching English as a foreign/second language to both undergraduate and postgraduate students. She is also a licensed internationally certified trainer and human resource consultant by the International Board of Certified Trainers (IBCT). Email: monosh2004@yahoo.co.uk Web: http://education.aau.ac.ae/en/edu-academic-staff/staff/view/192/ Dr Yehia A. Ibrahim is Professor Emeritus and Educational Consultant, Assiut University, Assiut, Egypt. Following obtaining his PhD degree, he was certified a Harvard IEM Diploma in Educational Management. Dr Ibrahim worked with several US universities as a visiting, adjunct or distinguished professor. In addition to his academic degrees and career, Dr Ibrahim is internationally accredited expert in several psychological and organisational disciplines and approaches. Dr Ibrahim has provided a number of professional guides in many fields, and regularly contributes articles to leading conferences, training journals and websites. Email: prof.dr.yehia.ibrahim@gmail.com Please cite as: Ibrahim, M. K. & Ibrahim, Y. A. (2017). Communicative English language teaching in Egypt: Classroom practice and challenges. Issues in Educational Research, 27(2), 285-313. http://www.iier.org.au/iier27/ibrahim.html |